Mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety disorders have become more prevalent, especially among young people. The demand for treatment is increasing and the prescriptions of some psychiatric drugs they have climbed.

These upward trends in prevalence parallel increasing public attention to mental illness. Mental health messages permeate traditional and social media. Organizations and governments are developing awareness, prevention and treatment initiatives with increasing urgency.

The growing cultural focus on mental health has obvious benefits. It raises awareness, reduces stigma and promotes help-seeking.

However, it can also come at a cost. Critics are worried social media locations incubate mental illness and that ordinary unhappiness is pathologized by the overuse of diagnostic concepts and “treatment talk“.

British psychologist Lucy Fulks argues that trends for increasing attention and prevalence are linked. her”Prevalence of inflation hypothesis” suggests that increasing awareness of mental illness may lead some people to be misdiagnosed when they experience relatively mild or transient problems.

Foulkes’ hypothesis implies that some people develop overly broad concepts of mental illness. Our research supports this view. In a new study, we show that concepts of mental illness have broadened in recent years – a phenomenon we call “Creep concept” – that too people differ in the range of their concepts of mental illness.

Why do people self-diagnose mental illnesses?

In our news studywe examined whether people with broad concepts of mental illness are, in fact, more likely to self-diagnose.

We defined self-diagnosis as a person’s belief that they have an illness, whether or not they have received the diagnosis from a professional. We assessed people as having a “broad concept of mental illness” if they judged a wide variety of experiences and behaviors to be disorders, including relatively mild conditions.

We asked a nationally representative sample of 474 US adults whether they believed they had a mental disorder and whether they had received a diagnosis from a health care professional. We also asked about other possible contributing factors and demographics.

Mental illness was common in our sample: 42% reported having a current self-diagnosed condition, the majority of whom had received it from a health professional.

Mental Health America/Pexels

As expected, the strongest predictor of reporting a diagnosis was experiencing relatively severe distress.

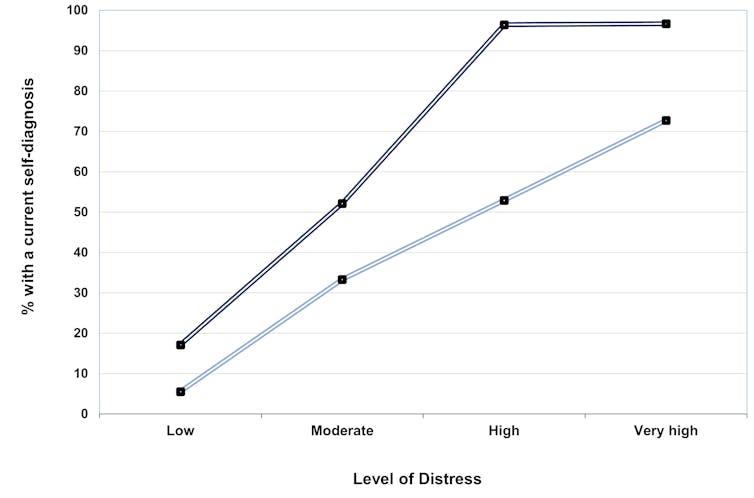

The second most important factor after distress was the broad concept of mental illness. When their levels of distress were the same, people with broad concepts were significantly more likely to report a current diagnosis.

The graph below illustrates this result. It divides the sample by levels of distress and shows the percentage of people at each level who report a current diagnosis. People with broad concepts of mental illness (the highest quarter of the sample) are represented by the dark blue line. Individuals with narrow concepts of mental illness (the lowest quarter of the sample) are represented by the light blue line. People with broad concepts were significantly more likely to report having a mental illness, especially when their distress was relatively high.

Provided by the authors

Individuals with greater mental health literacy and less stigmatizing attitudes were also more likely to report a diagnosis.

Two interesting further findings emerged from our study. People who self-diagnosed but had not received a professional diagnosis tended to have broader concepts of illness than those who had.

In addition, younger and politically progressive people were more likely to report a diagnosis, according to some previous research, and had broader concepts of mental illness. Their tendency to retain these more expansive concepts partly explained their higher diagnosis rates.

Why does it matter?

Our findings support the idea that extended concepts of mental illness promote self-diagnosis and may thus increase the apparent prevalence of mental illness. People who have a lower threshold for defining distress as a disorder are more likely to self-identify as suffering from a mental illness.

Our findings do not directly indicate that people with broad concepts are overdiagnosing or those with narrow concepts are underdiagnosing. Nor do they prove that they have broad meanings causes self-diagnosis or results in real increases mental illness. However, the findings raise significant concerns.

First, they suggest that increasing mental health awareness can they have costs. As well as enhancing mental health literacy, it can increase the likelihood that people will misidentify their problems as pathologies.

Improper self-diagnosis can have adverse effects. Diagnostic labels can be self-defining and self-limiting, as people believe that their problems are permanent; difficult to control aspects of who they are.

Karolina Grabowska/Pexels

Second, unwarranted self-diagnosis can lead people experiencing relatively mild levels of distress to seek help that is unnecessary, inappropriate, and ineffective. Recently Australian research found that people with relatively mild distress who received psychotherapy worsened more often than improved.

Third, these effects can be particularly problematic for young people. They are more likely to have broad definitions of mental illness, in part because social media consumption, and face mental health problems at relatively high and increasing rates. Whether extended concepts of illness play a role in youth mental health crisis remains to be seen.

Ongoing cultural changes encourage ever more expansive definitions of mental illness. These changes are likely to have mixed blessings. By normalizing mental illness they can help de-stigmatize it. However, by pathologizing certain forms of everyday discomfort, they may have an unintended disadvantage.

As we grapple with the mental health crisis, it’s important to find ways to raise awareness of mental illness without inadvertently inflating it.