University of Arizona researchers have revealed new insights into one of the most common complications faced by Parkinson’s disease patients: the uncontrollable movements that develop after years of treatment.

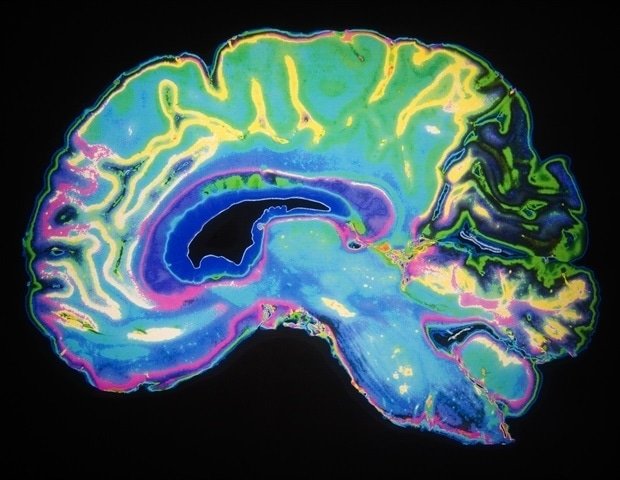

Parkinson’s disease – a neurological disorder of the brain that affects a person’s movement – develops when the level of dopamine, a chemical in the brain responsible for body movements, begins to decrease. To treat the loss of dopamine, a drug called levodopa is given, which is later converted to dopamine in the brain. However, long-term levodopa treatment causes involuntary and uncontrolled movements known as levodopa-induced dyskinesia.

A study published in the journal Brain has revealed new findings about the nature of levodopa-induced dyskinesia and how ketamine, an anesthetic, can help treat the challenging condition.

Over the years, a Parkinson’s patient’s brain adapts to levodopa treatment, which is why levodopa causes dyskinesia in the long term, said Abhilasha Vishwanath, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher in the U of A Department of Psychology.

In the new study, the research team found that the motor cortex—the area of the brain responsible for controlling movement—essentially “disconnects” during dyskinetic episodes. This finding challenges the prevailing view that the motor cortex actively generates these uncontrolled movements.

Because of the disconnect between cortical motor activity and these uncontrolled movements, there likely isn’t a direct connection, but rather an indirect way in which these movements are generated, Vishwanath said.

The researchers recorded activity from thousands of neurons in the motor cortex.

There are about 80 billion neurons in the brain and they hardly shut up at any point. So there are a lot of interactions between these cells that are going on all the time.”

Abhilasha Vishwanath, lead study author and postdoctoral research associate, U of A Department of Psychology

The research team found that the firing patterns of these neurons showed little correlation with dyskinetic movements, suggesting a fundamental disconnect rather than direct causation.

“It’s like an orchestra where the conductor goes on vacation,” said Stephen Cowen, senior author of the study and associate professor in the Department of Psychology. “Without the motor cortex properly coordinating the movement, the downstream neural circuits are left to spontaneously generate these problematic movements on their own.”

This new understanding of the underlying mechanism of dyskinesia is complemented by the team’s findings on the therapeutic potential of ketamine, a common anesthetic. Research has shown that ketamine could help disrupt the abnormal repetitive electrical patterns in the brain that occur during dyskinesia. This could potentially help the motor cortex regain control of movement.

Ketamine works like a one-two punch, Cowen said. It first disrupts these abnormal electrical patterns that occur during dyskinesia. Then, hours or days later, ketamine activates much slower processes that allow changes in brain cell connectivity and activity over time, known as neuroplasticity, that last much longer than ketamine’s immediate effects. Neuroplasticity is what allows neurons to form new connections and strengthen existing ones.

With a single dose of ketamine, beneficial effects can be seen even after a few months, Vishwanath said.

These findings take on added significance in light of an ongoing Phase 2 clinical trial at the U of A, where a team of researchers from the Department of Neurology is testing low-dose ketamine infusions as a treatment for dyskinesia in Parkinson’s patients. Early results from this trial look promising, Vishwanath said, with some patients experiencing benefits that last for weeks after a single course of treatment.

Ketamine doses could be modified in such a way that the therapeutic benefits are maintained with minimized side effects, Cowen said. Entirely new therapeutic approaches may also be developed based on the study’s findings regarding the involvement of the motor cortex in dyskinesia.

“By understanding the basic neurobiology underlying how ketamine helps these dyskinesias, we might be able to better treat levodopa-induced dyskinesia in the future,” Cowen said.

The study received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grants R56 NS109608 and R01 NS122805) and the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (grant ADHS18-198846).

Source:

Journal Reference:

Vishwanath, A., et al. (2024). Uncoupling of motor cortex with movement in Parkinson’s dyskinesia rescued by subanesthetic ketamine. Brain. doi.org/10.1093/brain/awae386.