If you’ve ever looked closely at IVF statistics, one number may strike you as particularly puzzling: Even when doctors transfer a chromosomally normal embryo, the kind most likely to succeed, a live birth happens only half of the time.

Sometimes implantation occurs but results in miscarriage. In many other cases, the embryo never implants at all.

For years, fertility science has focused heavily on embryo quality. And it’s understandable – the genetics of embryos matter. But what if we only asked half the question?

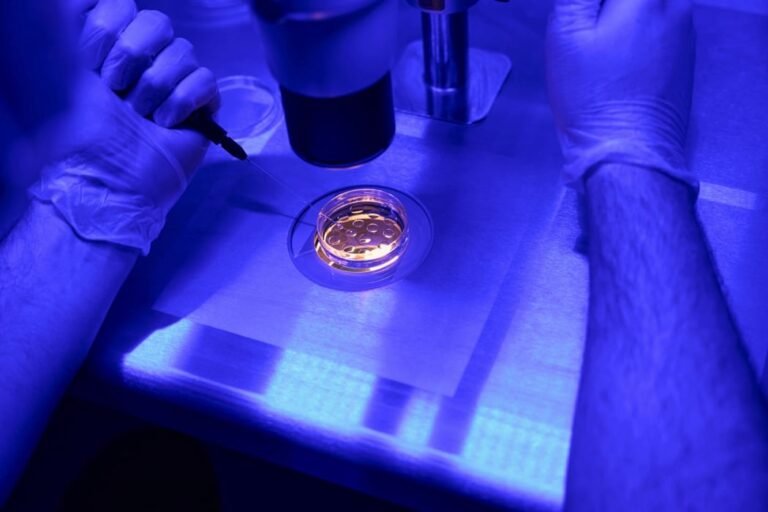

A new study by researchers at Rutgers Health and Michigan State University, published in JCI Insightsuggests that we may need to take a closer look at the uterus itself – specifically, how prepared it really is to receive a fetus.

Their findings show something as simple as it is profound: implantation is not just about the readiness of the embryo. The womb must also be ready – at a very precise moment.

Each menstrual cycle includes a short period known as the ‘implantation window’. This usually happens about six to ten days after ovulation, during what is called the mid-discharge phase.

Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone shift the lining of the uterus, the endometrium, from building mode to receiving mode. The tissue thickens earlier in the cycle, but thickness alone is not enough. At the right time, the cells within the lining must change how they function, communicate, and even how they physically interact with each other.

Everything must be aligned: timing, structure, signaling and support for a successful outcome.

Until now, scientists have not fully understood what this “ready” state looks like at the most fundamental, molecular level.

One of the strengths of this study is that the researchers did not start with infertility. Instead, they enrolled 30 women with regular cycles and proven fertility. Most participants self-identified as Black or Hispanic. This is a major step forward in a field that has historically underrepresented diverse populations.

The participants carefully tracked ovulation, and the researchers collected small samples of the lining of the uterus at specific, hormonally confirmed points in the cycle. Using both bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing, the team mapped how thousands of genes were turned on and off in different phases.

What they found was startling.

The largest molecular shift occurred during the midsecretion phase, precisely when implantation is supposed to occur.

And the most dramatic changes occurred in a specific group of cells.

The cells that stood out were glandular epithelial cells, found in the glands of the uterus. These glands produce substances that help nourish the fetus and coordinate implantation.

In fertile women, 556 genes were significantly activated in these glandular cells during the receptive window. The researchers named this group of genes the Glandular Epithelial Receptor Module, or GERM.

In practical terms, this 556 gene signature appears to represent a molecular ‘welcome signal’ from the womb.

When the team applied this GERM signature to previously published data sets of women with recurrent implantation failure or recurrent pregnancy loss, the results were consistent: the GERM score was lower in women struggling with infertility.

This suggests that in some cases, implantation may fail not because the embryo is defective, but because the uterine environment never fully transitions to its receptive state.

Clinically, uterine readiness is often assessed using ultrasound to measure endometrial thickness. In IVF cycles, a lining thinner than 7 mm is associated with lower pregnancy rates.

But the thickness tells us very little about what’s going on inside the cells.

Some clinics use transcriptional tools, such as the Endometrial Receptivity Array (ERA), which evaluates a set of genes to determine whether the uterus is pre-receptive, receptive or post-receptive. However, results from large trials were mixed and ERA did not consistently improve pregnancy rates.

This new research adds a more refined level of understanding. Rather than looking at overall tissue gene expression, it identifies which specific cells, particularly glandular epithelial cells, drive receptivity. About a third of the ERA genes overlapped with the new GERM signature, but the GERM panel significantly expands this list and narrowly focuses on the cells most involved in implantation.

In short, receptivity may be less about a general timing problem and more about whether these gland cells are doing their job correctly.

The study also looked at stromal cells, the structural cells that make up much of the lining of the uterus.

During the secretory phase, these cells begin a transformation known as dedifferentiation. They shift to a specialized state that supports pregnancy. Interestingly, the researchers also identified subsets of stromal cells that enter a controlled, temporary state of senescence, a type of programmed pause in cell division that appears to be part of normal engraftment biology.

In fertile women, there was a balance between enucleated and senescent stromal cells during the receptive window. In contrast, data sets from women with recurrent implantation failure showed disrupted ratios – including expansion of some senescent populations and reductions in key types of cellular damage.

This suggests that implantation may depend on a delicate cellular balance within the uterine lining, not just one marker or hormone level.

One of the most exciting findings involved communication between stromal cells and glandular epithelial cells.

During the midsecretory phase, signaling between these compartments peaked. Pathways related to collagen, part of the extracellular matrix, were particularly active. These pathways affect tissue stiffness, cell adhesion, and mechanical signaling.

The secretory glandular epithelium was the strongest recipient of these signals during the implantation window. Simply put, the stromal cells appeared to be speaking strongly to the glandular cells at just the right moment.

In women with infertility, this signaling axis appears to be disrupted.

Implantation, it turns out, is not just a chemical process. It is mechanical, structural and deeply coordinated.

Today, when a chromosomally normal embryo fails to implant, it is often described as inexplicable. But this study suggests there may be identifiable molecular causes.

If future research confirms these findings in IVF patients, clinicians may one day use a refined version of the GERM signature to:

- Identify patients whose uterine lining is not fully receptive

- Personalize your embryo transfer time

- Develop therapies that target key glandular pathways

- Potentially complement or regulate specific proteins involved in receptivity

The authors emphasize that this work is not yet ready for clinical use. The list of 556 genes needs to be narrowed down to something practical and future testing is needed.

But the direction is clear: assessing uterine readiness at a cell-specific level can improve how we understand implantation failure.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from this study is conceptual.

Implantation is not a one-sided event. A healthy fetus is necessary, but not sufficient. The matrix must undergo a highly coordinated, time-sensitive transformation. If this transformation is incomplete or incorrect, even a genetically normal embryo may fail to implant.

For people navigating IVF, this reframes the conversation. Failed implantation may not always be about the quality of the embryo. It may reflect a uterus that never fully entered its receptive state.

By mapping what actual receptivity looks like in fertile women in different populations, this research brings us closer to understanding the “black box” of implantation.

And in doing so, it opens the door to a future where fertility treatment focuses not just on creating strong embryos, but on ensuring the uterus is truly ready to receive them.