In recent years artificial intelligence has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing medical images. Thanks to advances in computing and the large medical data sets from which artificial intelligence can learn, it has proven to be a valuable aid in reading and analyzing patterns in X-rays, MRIs and CT scans, enabling doctors to make better and faster decisions, particularly in the treatment and diagnosis of life-threatening diseases such as cancer. In some settings, these AI tools even offer advantages over their human counterparts.

“Artificial intelligence systems can process thousands of images quickly and provide predictions much faster than human reviewers,” says Onur Asan, Associate Professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, whose research focuses on human-computer interaction in healthcare. “Unlike humans, AI does not tire or lose focus over time.”

However, many clinicians view AI with at least some degree of mistrust, mainly because they don’t know how it arrives at its predictions, an issue known as the “black box” problem. “When clinicians don’t know how AI generates its predictions, they’re less likely to trust it,” says Asan. “So we wanted to find out whether providing additional explanations can help clinicians and how different degrees of AI explanation affect diagnostic accuracy, as well as confidence in the system.”

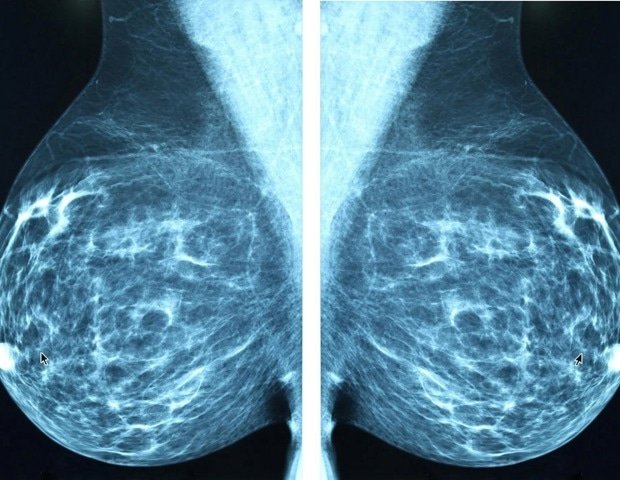

Working with his doctoral student Olya Rezaeian and assistant professor Alparslan Emrah Bayrak at Lehigh University, Asan conducted a study with 28 oncologists and radiologists who used AI to analyze breast cancer images. Clinicians were also given varying levels of explanation for their AI tool ratings. At the end, participants answered a series of questions designed to measure their confidence in the AI-generated assessment and how difficult the task was.

The team found that the AI improved diagnostic accuracy for clinicians over the control group, but there were some interesting caveats.

The study found that providing more thorough explanations did not necessarily produce more trust. “We’ve found that more explanation doesn’t equal more trust,” Asan says. This is because adding additional or more complex explanations requires clinicians to process additional information, taking their time and focus away from analyzing images. When explanations were more complex, clinicians needed more time to make decisions, which reduced their overall performance.

“Processing more information adds more cognitive workload to clinicians. It also makes them more likely to make mistakes and potentially harm the patient,” explains Asan. “You don’t want to add cognitive load to users by adding more tasks.”

Asan’s research also found that in some cases clinicians were over-trusting AI, which could lead to critical information being overlooked in the images and lead to patient harm. “If an AI system is poorly designed and makes some mistakes while users have a lot of confidence in it, some clinicians may develop a blind trust in believing that what the AI suggests is true and not look hard enough at the results,” says Asan.

The team presented their findings in two recent studies: The impact of artificial intelligence explanations on clinicians’ confidence and diagnostic accuracy in breast cancerpublished in his journal Applied Ergonomics on November 1, 2025 and Explainability and trust of artificial intelligence in clinical decision support systems: Effects on trust, diagnostic performance and cognitive load in breast cancer carewhich was published in International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction on August 7, 2025.

Asan believes that AI will continue to be a useful aid to clinicians in interpreting medical imaging, but such systems must be carefully constructed. “Our findings suggest that designers should be careful when creating explanations in AI systems,” he says, so they don’t become too cumbersome to use. In addition, he adds, proper user training will be needed, as human supervision will still be necessary. “Clinicians using AI should receive training that emphasizes interpreting AI outputs rather than simply trusting them.”

Ultimately, there should be a fine balance between ease of use and usefulness of AI systems, Asan notes. “Research finds that there are two main parameters for a person to use any form of technology – perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use,” he says. “So if doctors think this tool is useful for doing their job and it’s easy to use, they’re going to use it.”