• Research Highlights

Fragile X syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by the gene FMR1. It is the most common form of inherited intellectual disability and often coexists with other conditions such as autism and epilepsy.

New research has revealed important insights into the genetic mechanisms underlying FXS and related disorders. The study found that the disorders involve widespread silencing of many genes that play key roles in building tissue and proper brain function.

The research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the NIH Common Fund 4D Nucleome Program.

How are changes made in FMR1 gene driver in FXS?

The prevailing theory is that FXS involves changes in FMR1, a gene located on the X chromosome (one of the two sex chromosomes in humans). The first part of it FMR1 The gene consists of repeats of a specific DNA sequence called CGG. The CGG sequence can expand uncontrollably, leading to an excessive number of repeats. A regular length FMR1 The sequence has less than 40 CGG repeats. Instead, a mutation-length FMR1 The sequence has more than 200 CGG repeats.

When the FMR1 CGG reaches this mutational length, causing physical changes in the gene that silence its expression. As a result, FMR1 produces little or none of its protein, which is essential for healthy brain function. This is when FXS comes into play. People with FXS who lack the FMR1 protein can experience significant effects on their development , including intellectual and learning disabilities. speech and language difficulties; and social and behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity and anxiety.

However, changes to FMR1 alone do not represent the full spectrum of FXS symptoms, as demonstrated by mouse models in which the Fmr1 the gene is “knocked out” or genetically disabled. Previous research has also implicated a broader set of genetic mechanisms and gene locations FMR1 gagging.

What did the researchers do in the current study?

Jennifer Phillips-Cremins, Ph.D. , and first study authors Thomas Malachowski, MS, Keerthivasan Chandradoss, Ph.D., Ravi Boya, Ph.D., and Linda Zhou, MD, Ph.D., at the University of Pennsylvania led researchers to look beyond from the standard model of the FXS. They looked at whether human FXS tissues show changes in the genome (the complete set of genetic material [DNA]) or the epigenome (chemical modifications that affect gene expression without changing the DNA sequence) and whether these changes are specific to FMR1 or affect other genes as well.

The researchers combined multiple high-tech analytical methods, including molecular mapping, DNA imaging, epigenetic sequencing and genetic engineering. Additional computational approaches allowed them to integrate and find patterns in the large data sets they used.

The researchers examined genetic, epigenetic and imaging data in multiple human cell lines from people with FXS and people without the disorder. They looked genome-wide for changes that occur on both the X chromosome and non-sex chromosomes (known as autosomes ). In addition, they collaborated with the NIH NeuroBrainBank to collect post-mortem tissue from a region of the brain linked to FXS – the caudate nucleus – from people with and without the disorder.

These advanced methods have allowed researchers to examine the shape of DNA across the entire genome and how it folds into complex three-dimensional structures inside the cell nucleus (known as the three-dimensional genome). The folding of the genome in three-dimensional space reflects the packaging and interactions of its parts chromatin (the combination of DNA and protein that makes up the genome). Precise folding patterns in the 3D genome are critical for proper gene regulation and cellular function, and deviations from this structure are associated with genetic disorders such as FXS as well as many cancers.

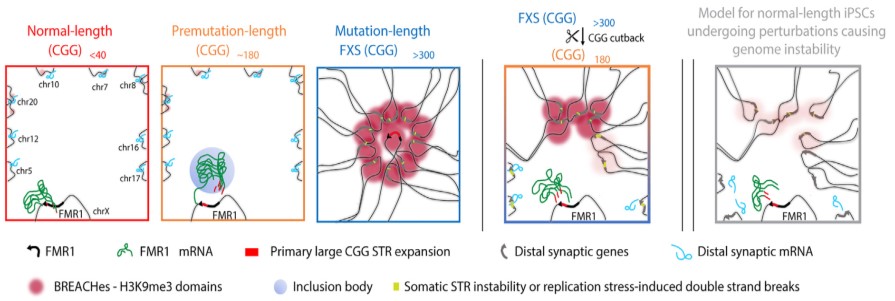

In all cell lines and tissues, the researchers compared its three versionsFMR1 CGG repeat that can occur:

- Normal length (5–45 CGG repeats)

- Premutation length (61–199 CGG repeats)

- Mutation length (>200 CGG, FXS repeats)

By analyzing the 3D genome and chromatin changes determined by CGG repeat length, researchers could find epigenetic changes and link them to the silencing of gene expression and genome instability that can lead to genetic disorders.

What did the results show?

The results confirmed, in cells and tissues from individuals with FXS, previously known changes associated with CGG expansion at mutant length, including epigenetic changes in FMR1 gene and silencing of FMR1 gene expression. The researchers also unexpectedly discovered more extensive changes in the DNA.

They found deposits of large pockets of a silent form of chromatin, known as heterochromatin, which folds very tightly and makes the gene less accessible. Pockets of heterochromatin extended much further FMR1. On the X chromosome, heterochromatin radiated outward to silence upstream genes FMR1 that are essential for nerve cell functions, such as circuit connectivity and synaptic plasticity, that could cause learning disabilities commonly experienced by people with FXS. On autosomal chromosomes, heterochromatin silenced multiple genes related to skin, tendon, and ligament integrity, which are clinically affected tissues in individuals with FXS.

The researchers also found severe DNA misfolding and potential break sites along the DNA sequence or slight extensions of other repetitive sequences within the heterochromatin. These types of higher-order genome folding patterns within cells are critical for proper gene function, so localized changes in genome structure are likely to be related to FXS beyond local silencing of FMR1.

The Cremins lab coined the term heterochromatin contact-anchored repeat expansion beacons, or BREACHes, to refer to the network of gene-silenced regions they discovered, characterized by severe chromatin misfolding and genome instability. The researchers suggest that the biological significance of BREACHes is the silencing of genes involved in processes essential to brain function, including those that control synaptic plasticity that allows the brain to change in response to learning and other dynamic situations. Silencing these genes may help explain many of the developmental differences seen in people with FXS.

Having generated broad structural and functional changes caused by the mutation length FMR1 CGG, the researchers looked at what happened when they shortened the repeat to a premutation length. They found that reducing CGG length led to the removal of heterochromatin in many of the DISRUPTIONS. This finding indicates that CGG repeat length is a major contributor to at least some of the severe and extensive 3D misfolding and gene silencing seen in FXS and related disorders. It also suggests that reverse engineering the mutant length CGG repeat could potentially prevent the occurrence of genome-wide defects seen in common genetic disorders in humans.

What do the results mean?

Together, the results reveal significant changes in genome structure associated with mutation length FMR1 CGG sequence. These changes, associated with problems in the way DNA folds and instability in the genome, cause genes with important roles in brain function to be silenced or inactive, helping to explain many of the symptoms seen in people with FXS.

The silenced regions spanned a network of widespread gene sites that the researchers called BREACHes. DISRUPTIONS were observed in multiple cell types and postmortem brain tissue from individuals with FXS and on both the X chromosome and multiple autosomal chromosomes. VIOLATIONS also included several genes not previously linked to FXS, offering new targets for future research.

According to the researchers, the discovery of VIOLATIONS fills an important missing piece in understanding FXS. The new finding helps explain the clinical picture and common symptoms of people with FXS, which could not previously be explained by the loss of FMR1 protein only. Because genome misfolding occurred not only in FXS cell lines but also in unstable cells in general, DISRUPTIONS may be important to the growing list of disorders characterized by unstable repeat expansions.

This study enhances the understanding of the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that contribute to FXS disease pathology. The results may, in time, have broad relevance for understanding, diagnosing and even treating the many disorders characterized by unstable repeat expansions or genome instability, including FXS and cancer.

Report

Malachowski, T., Chandradoss, KR, Boya, R., Zhou, L., Cook, AL, Su, C., Pham, K., Haws, SA, Kim, JH, Ryu, H.-S., Ge , C., Luppino, JM, Nguyen, SC, Titus, KR, Gong, W., Wallace, O., Joyce, EF, Wu, H., Rojas, LA, & Phillips-Cremins, JE (2023). Spatially coordinated heterochromatinization of long synaptic genes in fragile X syndrome. Cell, 186(26), 5840–5858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.019

Grants

MH120269 , MH129957 , DK127405 , DA052715 , HD098015 , NS129317