Machines still can’t think, but they can now validate your emotions, according to new research from New Jersey Institute of Technology assistant professor Jorge Fresneda.

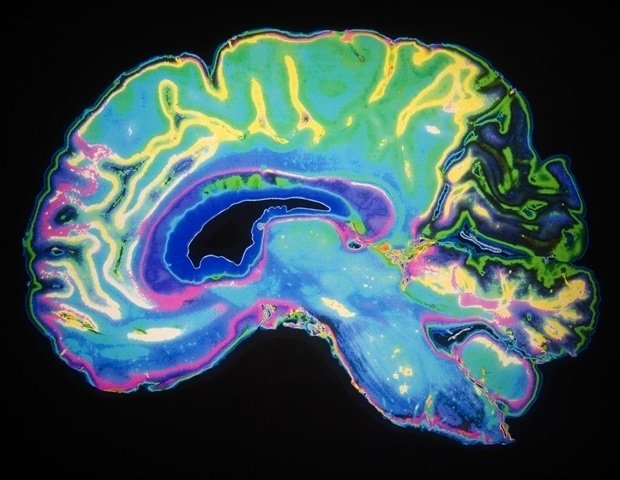

Fresneda began his career as a chemist and then became an expert in neuroanalysis. He studies how measurements of brain activity and skin conductance can predict a person’s emotions with high accuracy and how this information can be used in fields such as entertainment, management, marketing and well-being.

Neuromarketing is a subfield within marketing that uses sensors for marketing purposes, to inform managers and make better marketing decisions.”

Jorge Fresneda, Assistant Professor, New Jersey Institute of Technology

Collaborated with colleagues at NJIT’s Martin Tuchman School of Management -? Professor Jerry Fjermestad and PhD student David Eisenberg -; as well as Virginia Tech graduate research assistant Tanmoy Sarkar Pias, for publication Neuromarketing techniques to enhance consumer preference prediction earlier this year at the 57th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences.

Currently, most marketing surveys rely on people self-reporting their responses to everything from sales prices to dramatic videos. Fresneda found that if you add electroencephalogram (EEG) detectors, which detect brain waves, and galvanic skin response (GSR) sensors, which measure electrical conductance, then you can predict people’s feelings about marketing stimuli more accurately than their own self-report. This is determined by feeding the various sensor outputs through graphing algorithms and then comparing them to existing academic databases.

The field is not as far-fetched as it may sound. Modern EEG equipment, at non-healthcare levels, is small enough to pair with an ordinary Bluetooth headset. And GSR sensors, as Frankenstein-like as they sound, are already built into Samsung’s latest smartwatches. Fresneda added that one of the most impressive sensor networks may be deployed at North Jersey’s American Dream mall. While not fully used, he said it is potentially capable of collecting GSR data from smart devices or from radio frequency data transmitted by smart shopping bags and linking that information to social media profiles.

At a demo for retail store managers, opinions were mixed. Fresneda said all but two appreciated the technology’s ability to provide managers and sales staff with feedback on their own performance. Those opposed were very strong in their views on privacy issues. As a consumer, Fresneda said he would be willing to wear such technology, since most shoppers already allow companies like Amazon, Google and Facebook to track us. “If I get value in return, yes, of course. But you have to show me,” he said. “Otherwise, I’d be legitimately scared.”

“Furthermore, the same algorithms can be used to measure emotional responses, such as calmness or fear, which can potentially measure people’s reactions to various emotionally charged experiences,” their paper said. “Future research could use the same algorithm to predict consumer preferences or choices for different kinds of products, as well as in new product development, beyond music videos. Additionally, the same neural analysis could be applied for tracking people’s emotional states in other contexts, including customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, or even tracking employee productivity.”

Fresneda and her colleagues are now working on a follow-up journal article based on testing the technology’s application in areas such as consumer-oriented finance. It has been submitted for a quick review AIS transactions for human-computer interaction. The team is also in the early stages of developing patents that apply their research to healthcare and video games.