In experiments with healthy volunteers undergoing MRI imaging, scientists have found increased activity in two areas of the brain that work together to react and possibly regulate the brain when they “feel” tired and either close or continue to exercise.

Experiments designed to help detect various aspects of brain fatigue can provide a way for doctors to better evaluate and treat people who face overwhelming mental exhaustion, including those with depression and post -traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

A report on the study funded by NIH was published online on June 11 in Neuroscience newspaperdescribing the results in 18 women and 10 men healthy adult volunteers who gave duties to exercise their memory.

Our workshop focuses on how [our minds] Create value for effort. We understand less about the biology of cognitive duties, including memory and recall, than we do for physical duties, even though they both include many efforts. “

Vikram Chib, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the Medical School and researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Kennedy Krieger Institute

Regardless, Chib says, scientists know that cognitive tasks are tiring and relatively less about why and how such a fatigue is developed and plays.

The 28 study participants, who ranged from the age of 21 to 29, were paid $ 50 to participate in the study and told them that they could receive additional payments based on their performance and choices. All participants received a base MRI scan before the experiments began.

Their work memory tests, which took place while undergoing later magnetic resonance imaging of their brain, included a series of letters, in a series, on a screen and reminiscent of the position of certain letters. The farther a letter was in the order of letters, the more difficult it was to recall its position, increasing the cognitive effort spent. Participants received feedback on their performance after each test and opportunities to receive increasing payments ($ 1- $ 8) with more difficult recall exercises. Participants were also requested before and after each test to themselves the level of cognitive fatigue.

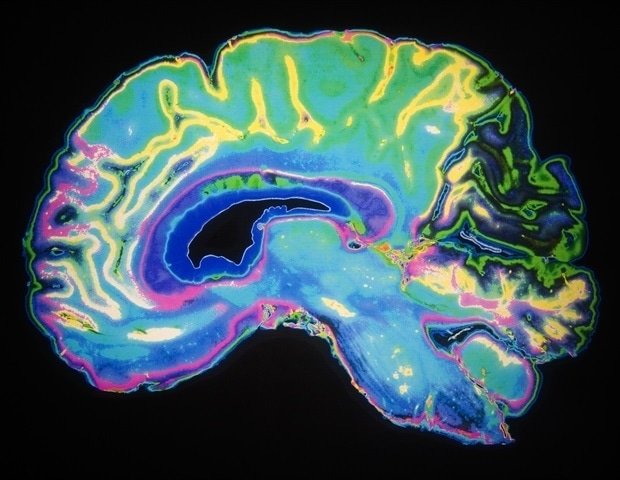

Overall, the results of the tests found increased activity and connectivity in two areas of the brain when participants reported cognitive fatigue: the right islet, an area deep in the brain associated with the feelings of fatigue and the dorsal lateral frontal cortex, and in the bark. For each participant, the activity in both positions of the brain during cognitive fatigue increased by more than twice the level of basic measurements taken before the testing.

“Our study was designed to cause cognitive fatigue and see how people’s choices are changing the effort when they feel fatigue, as well as identify sites in the brain where these decisions are made,” Chib says.

Specifically, Chib and members of the Grace Steward and Vivian Looi research team have found that financial incentives should be high, in order for participants to exercise increased cognitive effort, suggesting that external incentives are causing such an effort.

“This result was not completely amazing, as our previous work found the same need for motivation to promote physical effort,” Chib says.

“The two areas of the brain may work together to decide to avoid more cognitive efforts unless there are more incentives offered. However, there may be a difference between perceptions of cognitive fatigue and what is really capable of Chib.

Fatigue is associated with many neurological conditions, including PTSD and depression, says Chib. “Now that we probably have found some of the nerve circuits for cognitive effort in healthy people. We need to consider how fatigue in people’s brains are manifested,” he adds.

Chib says that it may be possible to use medication or cognitive behavioral therapy to combat cognitive fatigue, and the current study using decision tasks and functional magnetic resonance imaging could be a framework for the objective classification of cognitive fatigue.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging uses blood flow to measure wide areas of activity in the brain. However, it does not directly measure the activation of neurons, nor finer shades in brain activity.

“This study was performed in a magnetic resonance scanner and with very specific cognitive duties. It will be important to see how these results are generalized in other cognitive efforts and real world duties,” Chib says.

Research funding is provided by National Institutes of Health (R01HD097619, R01MH119086).

Source:

Magazine report:

Steward, G., et al. (2025). The neurobiology of cognitive fatigue and its influence on the effort based on effort. The neuroscience magazine. doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1612-24.2025.