The anxiety, a philosophical guide It is a book of healing philosophy. The purpose of the author Samir Chopra is to take us on the history of philosophy, pointing out those thinkers in the course that shaped its course.

In dealing with stress, then, this is not a list of recipes that we need to memorize and apply, but rather, a rich vocabulary that we can use in those silent but hectic moments we are discussing with ourselves.

Review: Anxiety, a philosophical guide – Samir Chopra (Princeton University Press)

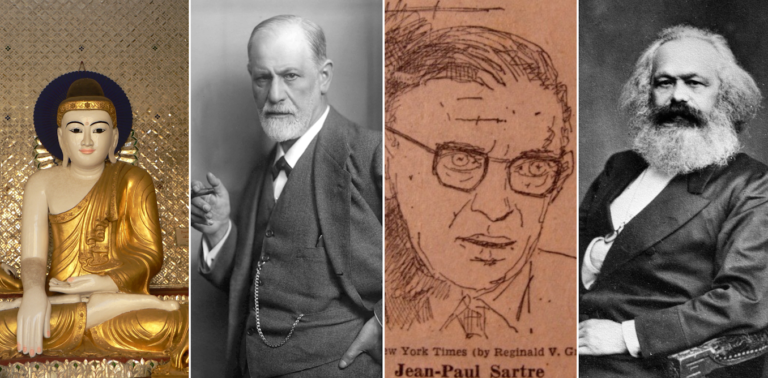

Instead of explaining our stress away, Chopra’s goal here is to cultivate the ability to see what stress shows. In this short text, he explores four schools of thought in relation to stress: Buddhism, existentialism, psychoanalysis and critical theory.

The book begins with a deeply personal and thoughtful narrative of Chopra’s own experiences with stress. Philosophical Advisor and Emeritus Professor of Philosophy in New York, Chopra writes about dealing with loss, his previous experiences in relationships and dealing with his pursuit of meaning throughout his life.

samirchopra.com

Tsopra writes openly for his struggle to face the loss of his father at an early age and later the loss of his mother. Seeking relief from his sadness, uninterrupted melancholy and anxiety about death, he turns to philosophy. This book is largely a product of the life experience of Tsopra and the way he accepted and lives with his anxiety with the help of philosophy.

It begins exploring how stress – and other emotions that are traditionally treated as deterrents such as anger – can be overcome by awareness of our “true nature”. These feelings appear in the Buddhist perception of ‘Dukkha’, which Chopra defines as

An acute anxiety, an existential discomfort, arising from a mental and emotional failure to deal with the bare data of existence.

In order to live quiet lives in front of our experience with Doukas, we must begin the Buddhist journey of “I come to see”. This is a long, difficult process of transforming the way we understand the world and our place in it.

In the extension of Dukkha on many pages, one finds a variety of well -made phrases that say almost the same thing. It is essentially that anything we believe is good, such as love or desire, is quickly overshadowed by the (re) discovery of our feelings of alienation, pain and weakness in the futility and absurdity of everything (though it says it better ).

At this point, after so much debate about despair and alienation, it is reasonable to wonder if we are talking about stress.

But Chopra confirms that existential anxiety is a kind of Dukkha because

It is the state of a foolish plasma that is confused with its nature, fools into the dark, harm himself and others by his illusions and ignorance, from his terrible reactions to the omnipresent possibility of deterioration, disintegration and death. life.

The “at the same time a heartbreaking and promising” solution lies within us, proposing, as thinking beings, in our minds.

With the help of meditation and awareness, Chopra argues, the Buddhist method for dealing with stress is to make room for it in our lives. We do not only relieve ourselves of stress then. On the contrary, we see it as an inevitable feature of our effort to live.

Existential stress

For the existentialists, as the name suggests, the root of our anxiety stems from our search for existential meaning.

The existentialists identified themselves as opposed to the essentials, who argued that there was an “end” (an end or purpose) for everything, including our own lives. On the contrary, existentialists claim, there is no meaning or purpose in life.

In Sartre’s famous lecture, existentialism as humanity writes:

We are left alone, without excuse. That’s what I mean when I say that man is doomed to be free. Doomed, because he did not create himself, but he is nevertheless free, and once he is thrown into this world he is responsible for what he does.

Human life is characterized by a naval abundance of freedom, with which we are doomed to do something. Chopra writes, “We are not just creatures that are free to act. We are creatures that we know we are free to act. ”

Anxiety, then, is born of this awareness of our freedom. For Sartre, authentic life, the well -known, is a life in which we courageously embrace this freedom in every choice, thinking and choosing on our own.

Goodreads

Chopra travels us through thinkers like Nietzsche; Kirkegor; Tillich and Heidegger To also argue that the existential message is to cultivate this courage, “to realize the brave ones for which we have already shown our ability” and “to set up ourselves as heroes in our minds to get up in the morning and turn around our face to the sun. “

Instead of trying to cover up our anxiety – and thus deny a fundamental characteristic of what it means to be – we must accept that in every choice, we re -create meaning for ourselves.

Psychoanalysis and critical theory

Chopra’s brief detour through psychoanalytic tradition brings us to Sigmund Freud. The latter, he argues, will double this existential call for courage, with the additional condition that the effort to suppress stress is in vain.

The oppressed anxiety comes to the surface only in parts of our lives, especially in our social life. Freud suggests a trained and mature response to stress involves a better understanding of how it is part of life, how it comes to our childhood and how it appears for us now.

There is also a specific category of stress attributed to the uncertainty caused by our ever -evolving social and political environments.

Chopra argues that this stress shows a prolonged fear of losing our financial position, along with a painful for our social and moral competence. This stress has not been helped, continues, by science and technology, which “harm us to climate change, mysterious pandemics and political dysfunction”.

Chopra is turning toward Herbert and Carl Marx To suggest that, unlike existentialists, this anxiety and alienation are not inevitable characteristics of the human condition. Rather, it is a product of the world we created.

Our experience of stress, continues, should stimulate activism and political criticism in the hope that we could make this world a little more bearable:

Fighting and dealing with stress requires acceptance, activism and meditation, an acute mixture of which may be the saving recipe to live with it.

Overall, Chopra does an excellent job by bringing difficult philosophical prospects to his discussion of stress. However, stress seems to have many roles in this book, roles that we usually attribute to other emotions or moods, such as alienation, question, alienation or regret.

By implicitly combining these many forms of experience, Tsopra is in danger of reading too much to these philosophers from time to time. The consequence of this is the ignorance of what makes these experiences unique.

However, sharing his own experience with anxiety, as well as linking us to the extensive philosophical literature where the stress is explored, Chopra and his philosopher interlocutors offer a strong and therapeutic insight: we are all united in the human condition he always has, and It will continue to be involved, meeting our restless self.