• Research Highlights

Changes in brain activity are known to contribute to the risk for depression. Could changing activity between brain regions also provide treatment for this common but serious mood disorder?

A neuroimaging study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health investigated whether a brain stimulation therapy known as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) could target areas deep in the brain through their surface connections. The study offers new evidence that stimulating deeper areas of the brain can reduce symptoms of depression and identifies a potential target for improved depression treatment.

What area of the brain did the researchers look at?

Researchers led by Desmond Oathes, Ph.D. and Kristin Linn, Ph.D. in the Center for Brain Imaging and Stimulation (CBIS) at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine studied an area of the brain called the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, or sgACC.

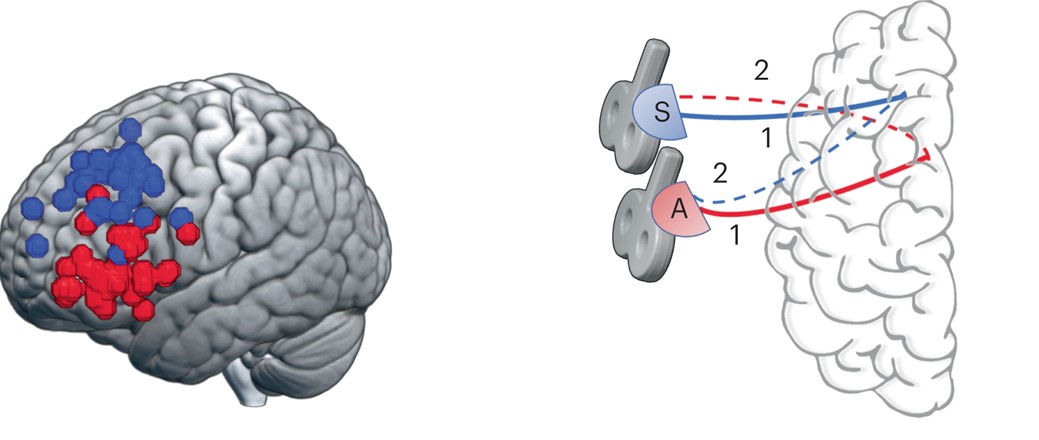

Located in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, the sgACC is important for regulating difficult emotions such as sadness and anxiety, and has been linked to risk for depression and other mood disorders. It is part of an emotion-related brain network that includes other sites in the prefrontal cortex. In previous studies, depressed subjects were more likely to improve if rTMS was applied to prefrontal sites highly connected to the sgACC, pointing to this connection as a promising target for rTMS treatment.

How did researchers deal with depression?

rTMS is a precise and non-invasive brain stimulation tool used to treat depression and other mental disorders. Brain stimulation treatments can play a critical role when other depression treatments such as medication and therapy have not worked.

rTMS can only directly stimulate the outer layers of the brain. However, brain regions are highly connected, allowing them to support complex functions such as emotion. It also suggests that reaching deeper brain regions, such as the sgACC, may be possible through stimulation of the surfaces connected to them. To achieve this, the researchers used imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to guide rTMS to deeper subcortical areas of the brain.

In a previous study , the research team used rTMS to successfully target the amygdala—a deep brain region associated with anxiety and fear. However, the antidepressant effects of rTMS are not fully understood, and researchers have yet to determine which brain regions to target for the greatest clinical improvement.

What did the researchers do in this study?

Thirty-six adults (18–54 years) with a diagnosis of depression and without psychiatric medication participated in this study. In an initial session, the researchers used fMRI to map each participant’s connectivity from the prefrontal cortex to the sgACC. They used this data to determine the exact stimulation site for each participant’s rTMS treatment to target their sgACC.

All participants then completed three days of rTMS treatment sessions. Before and after treatment, participants completed a short round of rTMS, followed by single TMS pulses during an fMRI brain scan. Taking the single step of stimulating the brain with TMS while recording the fMRI data allowed the researchers to record the brain’s response to rTMS and how it changed during treatment.

Clinicians also assessed participants’ depression symptoms before and after the rTMS sessions to determine whether their symptoms improved and, if so, whether this improvement was related to their response to sgACC.

Did rTMS treatment change sgACC response or depressive symptoms?

The researchers successfully used rTMS to stimulate the sgACC through its connections with the surface regions of the brain. This finding shows that fMRI can be used to guide rTMS to deeper areas of the brain.

After 3 days of rTMS treatment, participants’ depression symptoms improved by 34%, and anxiety symptoms improved by 32%. This change in symptoms corresponded to changes in sgACC activity, establishing a therapeutic role for rTMS in the treatment of depression through this pathway.

Importantly, change in depressive symptoms was predicted by initial sgACC response to TMS in the scanner. Participants with a stronger negative sgACC response to rTMS before treatment showed a greater reduction in depressive symptoms after treatment. Pre-treatment sgACC response was not related to change in anxiety symptoms, suggesting the specificity of this pathway to depression.

A greater improvement in depressive symptoms was also associated with a more positive (indicating a weaker) sgACC response after treatment. Consistent with previous studies, the researchers suggest that weakening the connection from the prefrontal cortex to the sgACC had a beneficial effect on depressive symptoms in this sample of adults with the disorder.

What do the results of this study mean?

This study offers critical insight into how rTMS engages neural circuits in the brain to help improve depression, highlighting an important link between the location of brain stimulation and change in depressive symptoms. Specifically, the researchers targeted and modulated the brain circuitry associated with depression using a safe, non-invasive means of both fMRI and rTMS.

According to the researchers, the findings are some of the strongest evidence to date that subgenital connectivity in the brain is a marker of antidepressant response. The identified pathway from the sgACC to the prefrontal cortex responded to rTMS and provided rapid relief of depressive symptoms. Incorporating fMRI-based brain mapping into rTMS sessions could make it possible to map outer brain regions accessible by rTMS to then stimulate deeper regions underlying depression and other disorders. This could eventually lead to more personalized or effective treatments for many mental disorders.

Although still preliminary, the potential clinical implications of this study are broad. A next step for the researchers is to replicate the findings in larger clinical trials of different people with and without depression and in people diagnosed with other mental disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Knowing that many brain regions and networks play a role in the clinical effects of rTMS, researchers also plan to examine other brain regions to improve treatment and better understand when, how, and for whom rTMS works best.

Report

Oathes, DJ, Duprat, RJ-P., Reber, J., Liang, X., Scully, M., Long, H., Deluisi, JA, Sheline, YI, & Linn, KA (2023). Noninvasive targeting, detection, and modulation of a deep brain circuit to alleviate depression. Nature Mental Health, 11033–1042. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00165-2