A rare “natural experiment” from the UK’s sugar rationing of the 1950s reveals that lower exposure to sugar in the first 1,000 days of life can lead to healthier hearts and fewer cardiovascular events decades later.

Research: Exposure to a sugar ration during the first 1000 days after conception and long-term cardiovascular outcomes: a natural experiment study. Image credit: ya_create / Shutterstock

In a recent study published in the journal BMJresearchers used a “natural experiment” from the post-war 1950s sugar rationing in the United Kingdom to investigate the long-term cardiovascular effects of diet in early life. Specifically, the study compared the heart health of adults born during the rationing period (low-sugar exposure cohort) with that of those born soon after it ended (higher-sugar exposure cohort).

The study’s findings revealed that people exposed to servings of sugar during the first 1,000 days had a significantly lower risk of heart attack, stroke and heart failure decades later, highlighting a strong link between sugar intake in early life and long-term heart health. These findings suggest that lower sugar exposure in early life may confer lasting cardiovascular benefits, thus adding to the evidence supporting limiting added sugars during pregnancy and infancy.

Background

The “first 1,000 days” is a popular term in the medical community, referring to the period from conception to a child’s second birthday. A growing body of research increasingly recognizes this period as a critical window for fetal development, with diet and other environmental factors potentially programming an individual’s lifelong cardiometabolic health.

Parallel studies in animal models suggest that excessive exposure to sugars in early life can lead to adverse chronic health outcomes. Unfortunately, while direct human evidence of the long-term benefits of sugar restriction in early life is limited, the high levels of added sugars in many baby and toddler foods are a major concern.

About the study

The present study aims to address this knowledge gap and enhance understanding of added sugar in infant diets by employing a ‘natural experiment’ design, exploiting a unique historical event: the end of the post-war sugar rationing in the UK (September 1953). The study aims to determine the relationship between early life sugar intake (availability, used as a population-level proxy for individual exposure) and adult life cardiovascular health.

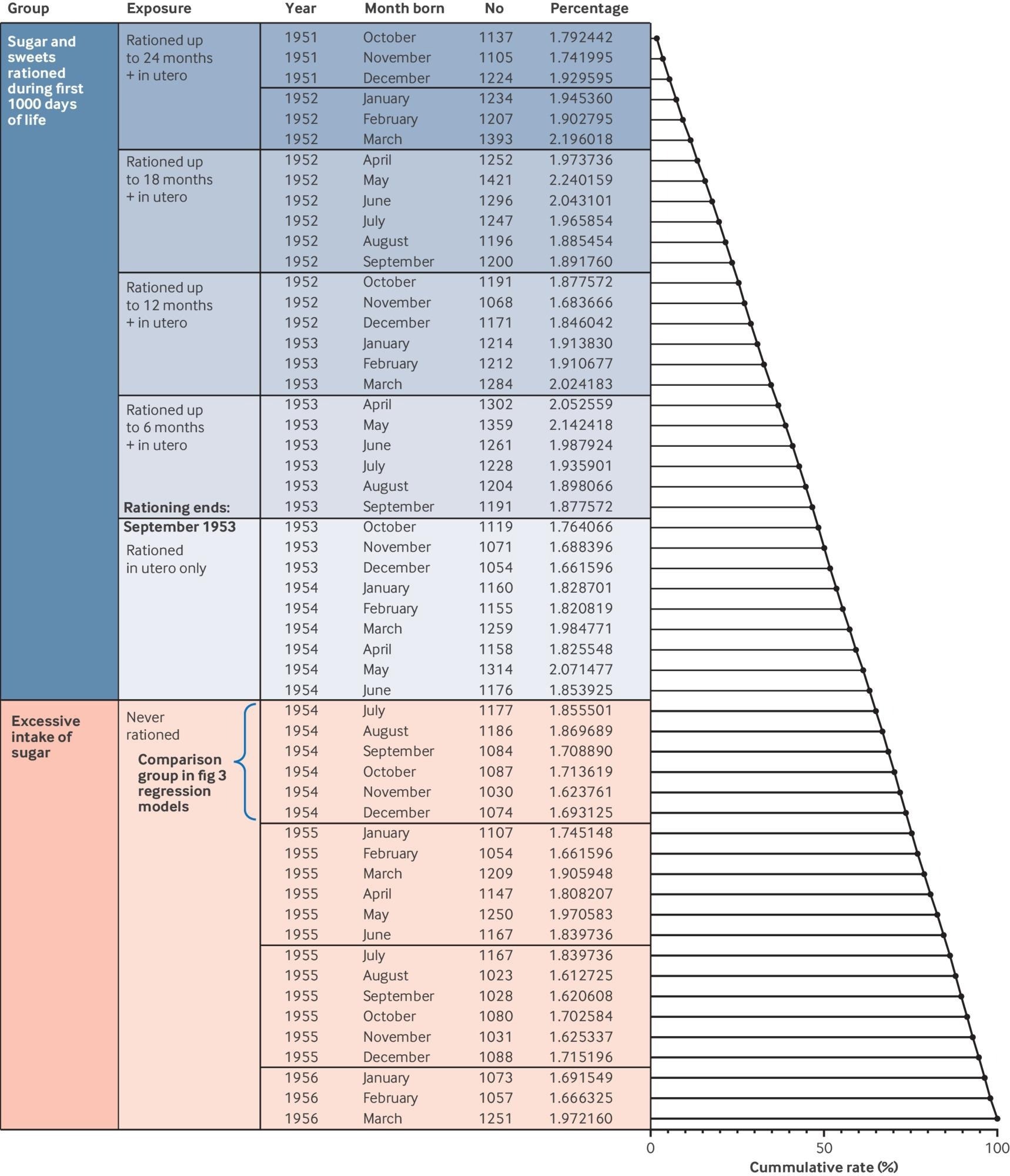

Study data were retrospectively obtained from United Kingdom Biobank (UKB), an extensive population health database, and included a cohort of 63,433 participants born between October 1951 and March 1956. This particular time frame was chosen because it perfectly encapsulates the end of the UK’s national sugar rationing in September 1953.

Notably, unlike most policy changes that take years or even decades to implement, the UK’s national sugar rationing caused a sharp and immediate increase in public sugar consumption, effectively creating two distinct groups.

The included study participants (n = 63,433) were quasi-experimentally divided into groups (subcohorts) based on their date of birth, which determined their level of exposure to servings of sugar during the critical first 1,000-day window. These groups ranged from those exposed in utero and for the first two years of life (born 1951-1953, low-sugar exposure cohort) to those never exposed (born late 1954-1956, higher-sugar exposure cohort).

Study data of interest included sociodemographic information (age, sex, race/ethnicity, etc.) and electronic health records (EMR), the latter of which were used to monitor the incidence of six primary outcomes: cardiovascular disease (CVD), myocardial infarction (heart attack), heart failure, atrial fibrillation, stroke and mortality from cardiovascular disease. A subset of this cohort also underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the effects of differential sugar intake on subclinical cardiac structure and function.

Distribution of sample births by calendar months and exposure to portion sugar. The sugar portion group is depicted in blue. The group that was never exposed to a sugar ration is represented in orange. The first group of those never exposed to a sugar ration is labeled and used as a control group to assess the association of early life ration exposure with cardiovascular outcomes

Study findings

The study results revealed that the more a person was exposed to a serving of sugar in early life, the lower their risk of cardiovascular problems in adulthood, establishing a dose-dependent association between early sugar exposure (first 1,000 days) and long-term cardiovascular health.

The analyzes showed that the most protected group consisted of those exposed to ration in the womb and during the first one to two years of life. Compared to people never exposed to ration, this group showed significantly reduced risks CVD (20% lower risk [HR 0.80]), myocardial infarction (25% lower risk [HR 0.75]), heart failure (26% lower risk [HR 0.74]), atrial fibrillation (24% lower risk [HR 0.76]), stroke (31% lower risk [HR 0.69]), and CVD-related mortality (27% lower risk [HR 0.73]).

Most importantly, these calculated risk metrics were found to translate into measurable real-world cardiovascular benefits, on average, the most exposed group developed CVD about 2.53 years later than the unexposed group, a finding supported by cardiovascular MRI data, which also found that the portioned group had a small but significant increase in left ventricular ejection fraction (~0.84 percentage points higher) and stroke volume index (~0.73 mL/m² higher), both indicators of improved heart function.

All-cause mortality was also lower in the highest exposure group (parametric model HR ~0.77).

Mediation analysis of the study showed that diabetes and hypertension together mediated about 31% of the association, while birth weight accounted for about 2%, suggesting that these mediators do not fully explain the observed relationship, but causality cannot be inferred.

Findings were robust in competing risk models, absent placebo effects (osteoarthritis, cataract) and directionally supported in an external UK cohort (ELSA), with null results among contemporary non-UK-born controls.

The authors also noted that the UK Biobank sample tends to represent a healthier subset of the general population, which may limit the generalizability of these findings to wider populations.

conclusions

The present study provides compelling, long-term, population-scale evidence of a relationship between early-life (dose-dependent) sugar intake and later life CVD results. Importantly, the benefits appear to extend beyond the effects of diabetes and hypertension, suggesting that early sugar restriction may have a more direct or unmeasured protective effect on heart health.

The findings highlight that the first 1,000 days of life are a critical developmental window for dietary interventions that may reduce future CVD risk, while emphasizing that causal inference is limited by the observational design.

Journal Reference:

- Zheng, J., Zhou, Z., Huang, J., Tu, Q., Wu, H., Yang, Q., Qiu, P., Huang, W., Shen, J., Yang, C., & Lip, GYH (2025). Exposure to a sugar ration during the first 1,000 days after conception and long-term cardiovascular outcomes: a natural experiment study. BMJ391, e083890. DOI 10.1136/bmj-2024-083890.