Exposure to bright light synchronizes the central circadian clock in our brain, while proper meal timing helps synchronize the timing of different clock genes throughout the rest of our body.

One of the most important discoveries of recent years he’s got was the discovery of “peripheral clocks”. We have known for decades about the central clock — the so-called suprachiasmatic nucleus. It sits in the middle of our brain just above where our optic nerves cross, allowing it to respond to day and night. Now we know there too is semi-autonomous clocks in almost every organ in our body. Our heart works with a clock, our lungs work with one, and so do our kidneys, for example. In fact, up to 80 percent of the genes in our liver are is expressed in a circadian rhythm.

Our entire digestive system is, very. The rate at which our stomach empties, the secretion of digestive enzymes, and the expression of transporters in our intestinal lining for the absorption of sugar and fat are cycled around the clock. The same goes for our body fat’s ability to absorb extra calories. The way we know these circles is is driven from local clocks, rather than being controlled by our brains, is that you can take surgical biopsies of fat, put them in a petri dish, and watch them continue to emit a rhythm.

All this talk about the clock isn’t just biological curiosity. Our health may depend on keeping everything in sync. “Imagine a child game on a swing.” Imagine yourself pushing, but you are distracted by what is happening around you on the playground and stop paying attention to the timing of the push. So you forget to push, or you push too early or too late. What Out of sync, the swing becomes erratic, slows down or even stops. This happens when we travel across time zones or have to work the night shift.

The “impulse” in this case is the bright marks falling on our eyes. Our circadian rhythm is meant to get a “boost” from bright light every morning at dawn, but if the sun rises at a different time or we’re exposed to bright light in the middle of the night, this can throw our cycle out of sync and out of sync. to feel inadequate. This is an example of a mismatch between the external environment and our central clock. Problems can also arise from a misalignment between the central clock in our brain and all the other organ clocks throughout our body. An extreme illustration of this is a remarkable set of experiments suggesting that even our poop can get jet lagged.

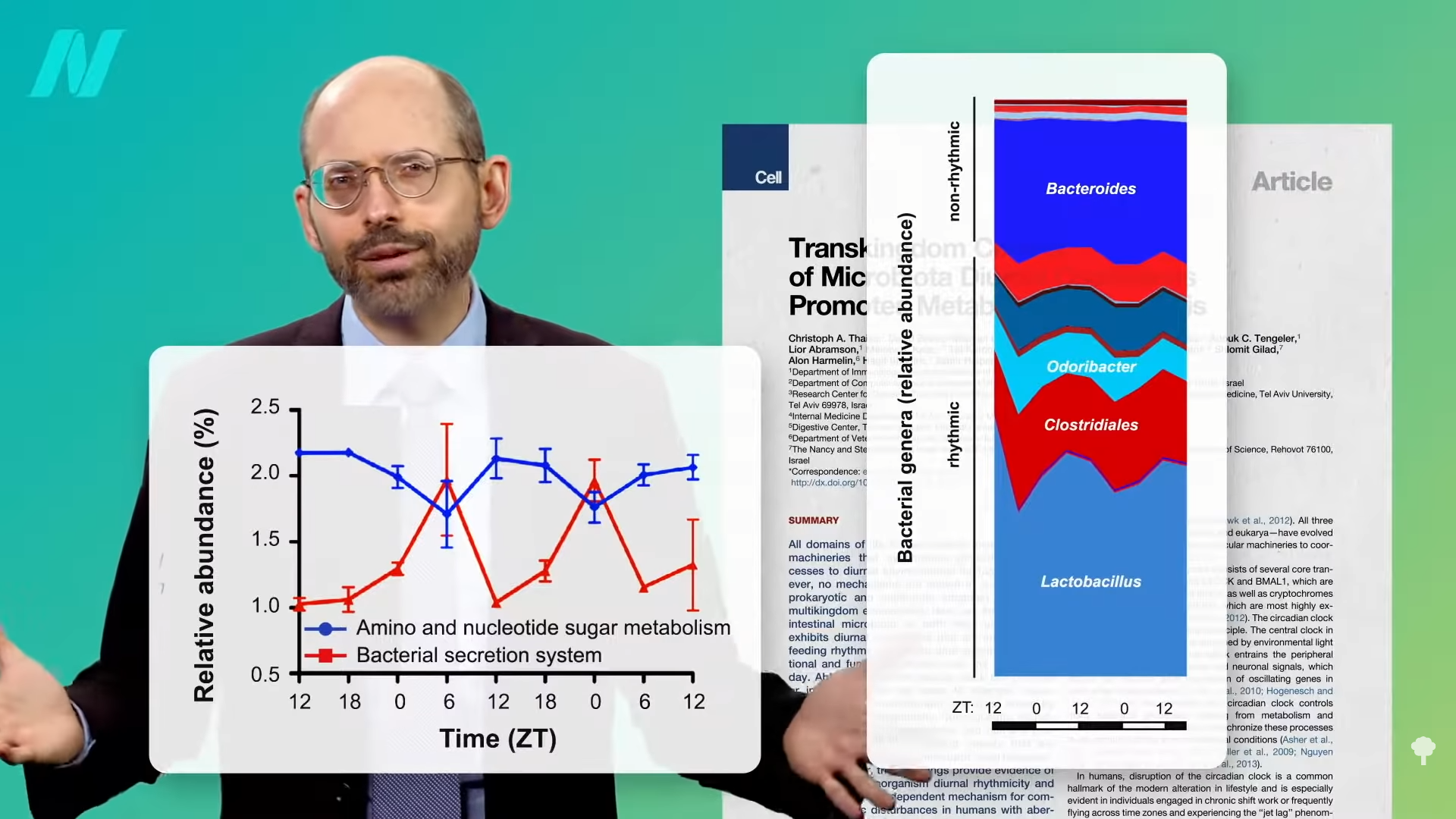

As you can see below and at 2:31 in my video How to synchronize your central circadian clock with your peripheral clocksour microbiome seems to I have its own circadian rhythm.

Even though bacteria are down where the sun don’t shine, there is a daily fluctuation in both bacterial abundance and activity in our colon, as you can see in the chart below and at 2:43 in my video. Interesting, but who cares? Everyone should.

Check this out: If you put people on a plane and fly them halfway around the world, then feed their poop to mice, those mice get fatter than mice fed feces before the flight. The researchers suggest that the fattening flora was a consequence of “circadian misalignment”. Indeed, many lines of evidence now involve “chronism”—the condition in which our central and peripheral clocks drift out of sync—as game role in conditions such as premature aging and cancer, as well as fluctuates in others such as mood disorders and obesity.

Exposure to bright light is the synchronizing oscillating drive for our central clock. What leads our internal organ clocks that are not exposed to daylight? Food intake. This is why the timing of our meals can be so important. Researchers was removed all external timing cues by keeping study participants in constant dim light and found that you could effectively uncouple central from peripheral rhythms simply by varying meal times. They took blood samples every hour and biopsies of the subjects’ fat every six hours to demonstrate the resulting metabolic derangement.

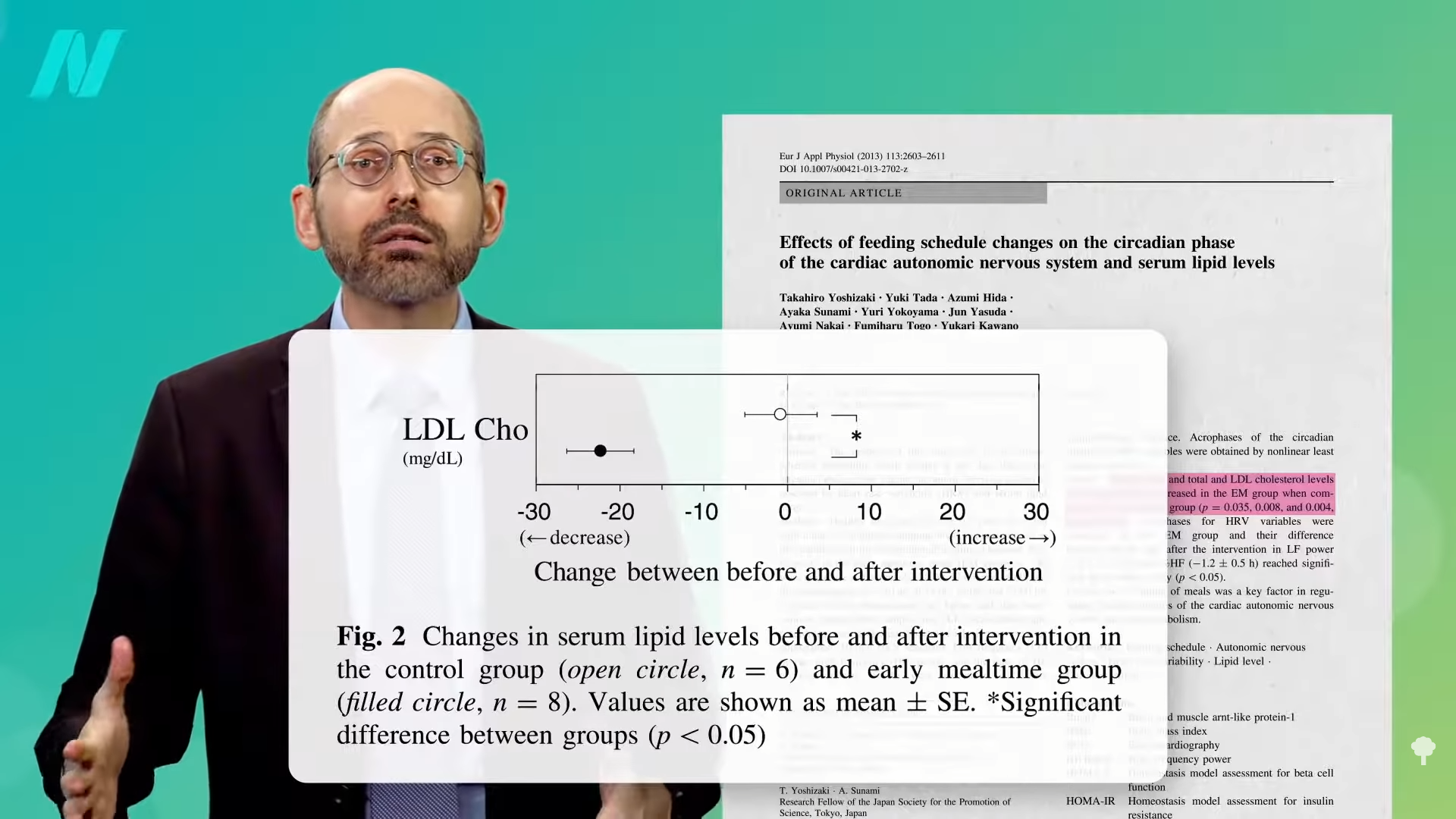

Just as morning light can help synchronize the central clock in our brains, morning meals it can help synchronize our peripheral clocks throughout the rest of our body. Skipping breakfast disrupts the normal expression and rhythm of these same clock genes, which coincides with adverse metabolic effects. Fortunately, they can be reversed. I get a group that used to skip breakfast and have them eat three meals at 8:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m., and their cholesterol and triglycerides improved, compared to eating meals five hours later at 1:00 p.m., 6:00 p.m., and 11:00 p.m. There is circadian rhythm in cholesterol synthesis in the body, which is also “strongly influenced by food intake.” This is demonstrated by the 95 percent drop in cholesterol production in response to a day of fasting. That is why a shift in meal times of just a few hours can results in a 20-point drop in LDL cholesterol thanks to eating meals earlier, as you can see below and at 5:00 video.

If exposure to light and meal times help to synchronize everything, what happens when circumstances prevent us from following a normal cycle of the day? We will learn inside The metabolic damage of night shifts and irregular meals. If you’re just getting into the series, be sure to check out the related posts below.