Scientists have identified the brain activity associated with internal speech-the silent monologue on the heads of people and successfully decoded it with accurately up to 74%. Publications on August 14th at Cell Press Magazine CellTheir findings could help people who are unable to speak with headphones more easily communicate using brain-computer interconnection technologies (BCI) who begin to translate internal thoughts when a participant says a password in their heads.

This is the first time we have managed to understand what brain activity is when you are thinking of talking. For people with serious speeches and motor damage, BCIs who can decode the internal speech could help them communicate much easier and more natural. ”

Erin Kunz, Head of Stanford University writer

BCIS recently appeared as a tool to help people with disabilities. Using sensors implanted in areas of the movement of movement, BCI systems can decode movement -related nerve signals and translate them into actions such as moving a prosthetic hand.

Research has shown that BCIS can even decode the attempt to talk among people with paralysis. When users are naturally trying to speak loudly with the involvement of sound -related muscles, BCIS can interpret the resulting brain activity and type what they are trying to say, even if the speech itself is incomprehensible.

Although communication with the help of BCI is much faster than older technologies, including systems that monitor users’ eye movements to type in words, trying to speak may still be tiring and slow for people with limited muscle control.

The team wondered if the BCIS could decode the internal speech.

“If you just have to think about speech instead of really trying to talk, it’s potentially easier and faster for people,” says Benyamin Meschede-Krasa, co-starring author of Stanford University.

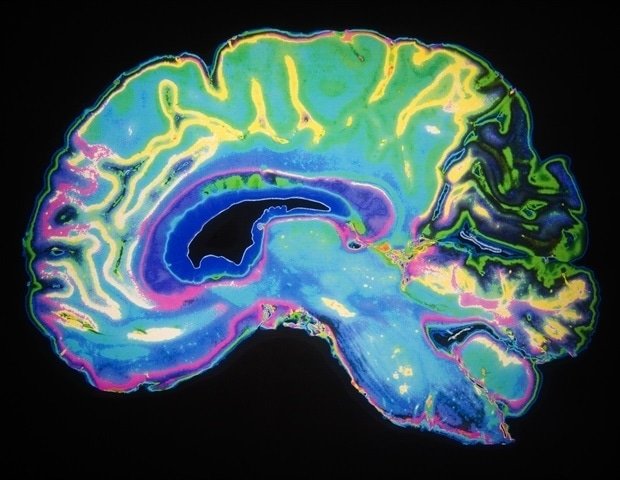

The group recorded nervous activity from microelectrodes implanted in the brain area of the motor cortex-A responsible for speaking-in-laws with severe paralysis either by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or from a stroke. The researchers asked the participants to try to speak or imagine by saying a set of words. They found that the speech attempt and internal speech activate the overlapping areas in the brain and cause similar nervous activity standards, but the internal speech tends to show a weaker size of activation as a whole.

Using the internal speech data, the team trains artificial intelligence models to interpret fantastic words. In a demonstration of the idea, the BCI could decode the fantastic sentences from a vocabulary of up to 125,000 words with a accuracy rate of up to 74%. The BCI was also able to get what some internal speech participants had never been ordered to say, such as numbers when participants were invited to gather pink circles on the screen.

The group also found that while the speech attempt and internal speech produce similar patterns of nervous activity in the motor cortex, they were different enough to reliably distinguish each other. Senior writer Frank Willett at Stanford University says researchers can use this distinction to train BCIS to completely ignore the internal speech.

For users who may want to use the internal speech as a method for faster or easier communication, the team also displayed a password controlled mechanism that would prevent BCI from decoding the internal speech unless temporarily unlocked with a selected keyword. In their experiment, users could think of the phrase “Chitty Chitty Bang” to begin decoding internal speech. The system recognized the password accurately over 98%.

While current BCI systems are not able to decode the internal speech of free form without making significant errors, researchers say that more advanced devices with more sensors and better algorithms can be able to do so in the future.

“The future of BCIS is bright,” says Willett. “This project gives a real hope that BCIS speech can one day restore communication that is so fluent, natural and comfortable as a conversation.”

Source:

Magazine report:

Kunz, Em, et al. (2025). Internal speech on the motor cortex and consequences for speech neuroproductions. Cell. Doi.org/10.1016/J.cell.2025.06.015.