Part 5: Our house attracted death like a magnet

Our house attracted death like a magnet. In 1949, the same year my father was committed to Camarillo State Hospital, Holly, a close family friend, shot himself. I remember going to the service, confused and scared, but no one talked about why he died. However, everyone knew it was suicide. Years later I was searching through our attic and found nine of my father’s diaries written between 1946 and 1949. They were a gold mine for me, giving me insight and understanding into my father’s inner world, his hopes, dreams and demons. doubt. he struggled with it all his life.

There were several entries about Holly’s friend, a fellow writer, written three years before the death. He described the pressures Holly faced in the years leading up to his suicide.

“When a subject possesses you as Holly’s subject possessed him, good writing must result. You begin to see and understand what the heroic work of the novel is, how much guts, endurance, endless sweat and constancy you need.”

My father also felt the same power driving Holly to despair.

“How alike me and Holly are in our basic state of life. We’re both struggling to make ends meet, feeling a raging hatred within us, the hot breath of need burning down our throats, the constant finger poised to stick in our noses and tell us “time’s up.” It’s too late.’ Now you have to make it by working at what you hate. The hands of the clock show twelve.’

The same year that Holly died, my best friend, Woody, drowned in the river near our house. He was my best friend and his sudden death left me feeling sad and lonely. I tried to talk to my mother about my feelings, but she was caught up in her own fears. “God, I’m so glad you didn’t go to the river with him” my mother said as she hugged me tightly. “That could have been you.” I put my own feelings aside and tried to reassure her that I was fine and wouldn’t go near the river.

My mother was preoccupied with her own death. From the moment I was born, when she was thirty-five, I knew my mother was going to die. He talked about it all the time. “I just hope I’m around to take you to high school” he would tell me. Her voice was always light and cool, but it chilled me to the bone. When she was still around when I went to high school, she wasn’t reassured, she just carried her impending death a little further down the line. “I just want to see you go to college before I die” he would tell me.

I was seven when “The Forester” came for a visit. He sold life insurance, but his story made it seem like he was here to provide protection and support. Although we had little money for the necessities, my mother bought the whole package. My mother signed up for insurance on herself so I would be taken care of when she died. He also bought me an insurance policy because “it’s never too early to think about your wife and children.” As a dutiful son, I was proud to have an insurance policy to take care of my family when I died…while still in first grade.

I began to see death as a companion, a deadly twin that shadowed my dreams. I slept alone and had developed a ritual that allowed me to sleep. I had to arrange the sheets and blankets in such a way as to create a safe cocoon and when it was right to sleep. But every night I would see the same dream:

I wake up and get out of bed. I walk from my bedroom to the dining room and from there to the kitchen and living room. Somewhere along the way a dark figure jumps out holding a long knife. I immediately start running. I know that if I can get back to my bed, I will be safe. But I never succeed. I get stabbed and wake up screaming.

My mother never seemed to hear the screams and I didn’t want to worry her. When I finally told her the dream, she gave no idea as to the cause, nor did she seem concerned. The dreams continued, but I never discussed them with her or anyone. However, my own preoccupation with death took hold in my subconscious, only to surface many years later in college. I took my girlfriend to see A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Eugene O’Neill’s autobiographical masterpiece about growing up in a crazy, dysfunctional family. My girlfriend hated it. I felt like I had found a kindred spirit that was telling my story. A small section spoke deeply about my life up to that point.

In the play, as his family unravels around him, the youngest son, Edmund, tries to understand his place in the family drama. It says:

“It was a big mistake, when I was born a man I would have been much more successful as a seagull or a fish. As it is, I’ll always be an outsider who never feels at home, who doesn’t really want and isn’t really wanted, who can never belong and who always has to be a little in love with death!”

After I stopped visiting my father in Camarillo, my mother and I never spoke of him. It was as if he was dead or had never existed. We became a family of two. My mother never mentioned him, and I told the kids at school that “my father died,” which gave me a little sympathy that I never felt when I said he had a “nervous breakdown and was in a mental hospital.”

Life Lesson: When adults deny the reality of depression and suicide, children are left to deal with their confused emotions on their own.

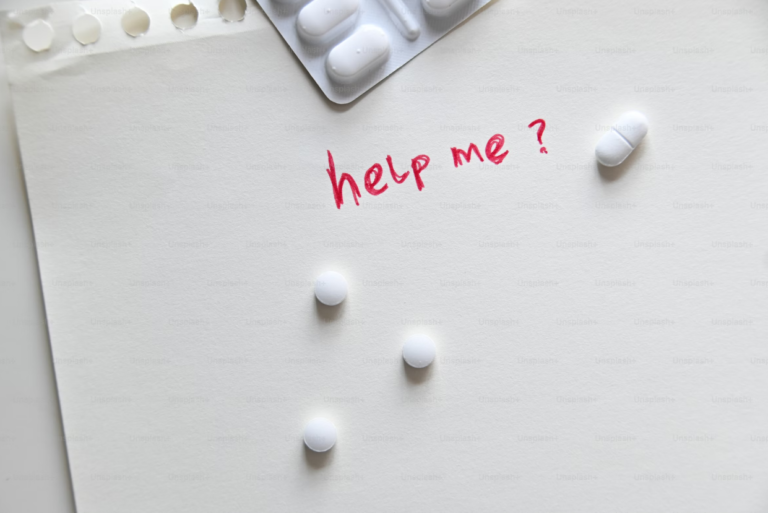

When my middle-aged father overdosed on sleeping pills and was committed to the state mental institution, the adults in my life couldn’t deal with the reality of his feelings of despair. My mother was consumed by her own fears and denial and chose not to visit him in the hospital. He assigned my uncle and I to make the weekly visits to see my father. Family and friends did not talk openly about the suicide death of my father’s close friend, Holly, another struggling creative artist.

Male suicide rates are four times higher than female rates and are even higher as men get older. When we deny our early trauma, it often turns into depression, which can lead to suicide.

Life Lesson: Although depression and hopelessness that can lead to suicide can affect anyone, it is more prevalent among sensitive, creative, men and women.

Kay Redfield Jamison is Professor of Psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. He is a co-author of the standard medical text on bipolar disorder and a national best-selling author An Unquiet Mind: Memoir of Moods and Madness, Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide, and other books.

In Touch with Fire, begins by quoting the poet Lord Byron as he talks about himself and other creative types.

“We’re all crazy”

Byron said of himself and other creatives.

“Some are affected by cheerfulness, others by melancholy, but all are more or less moved.”

Where has depression appeared in your life or in the lives of people you love? Do you consider yourself a creative person? Do you see a connection between your creativity and the times you’ve felt down or depressed?

I look forward to hearing from you. New training opportunities coming in 2025. Drop me a note at Jed@MenAlive.com if interested.

If you appreciate these articles, please share them. It is my labor of love. If you’re not already a subscriber, feel free to do so here.