In patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), regular immunoglobulin replacement therapy was not associated with a reduced risk of severe infections that require hospitalization, according to a study published in the The blood progresses.

This is the first large, real study that follows CLL patients who regularly receive immunoglobulin replacement. Given the high cost and its variable use in clinical practice, this is a crucial issue from a political, economic and clinical perspective. ”

Sara Carrillo de Albornoz, Head of Study Author, Health Economist and PhD candidate at Monash University, Australia

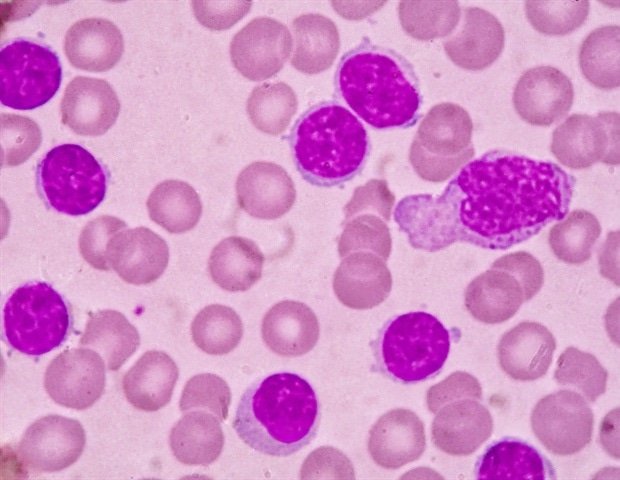

CLL, a common type of leukemia in adults, disrupts the production of antibodies by the body (immunoglobulin molecules) that fight infections. As a result, patients with CLL are often sensitive to severe and potentially life -threatening infections. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy is often used to strengthen antibodies in an attempt to reduce the risk of infection.

“Many of the studies that support the use of immunoglobulins to reduce infections in patients with blood cancer dating from thirty years and CLL treatment has progressed significantly since then,” said study author Erica Wood, AO, MD, Professor at Monash University. “While immunoglobulins are likely to benefit some patients, there remains a critical need for a better understanding of the extent of this benefit, which is more likely to benefit and how long these patients should receive treatment.”

The research team used linked data from the Victorian Cancer Registry, the Death Index and the assisted sets of episodes, which included long -term hospital and death data for patients aged 18 years or older diagnosed with CLL between January 1, 2008. The total study group was 6,217 patients, with 5,464 (87.9%) not to treat immunoglobulin replacement and 753 (12.1%) who received at least one dose during the follow -up period, which averaged 6.9 years.

Throughout the 14 -year follow -up period, among patients who remained alive, the percentage of people who received immunoglobulin replacement increased from 2% in the first year after diagnosis to 8.8% during the year during this period, 2,191 out of 6,217 (35.2%). Between the full study of the study, patients with severe infection were much more likely to begin to receive immunoglobulin replacement treatment at 30 days after their infection, at a rate of 0.075 per person (a unit that measures the appearance per person observed for one month), compared to only 0.001 per person. Of the 753 patients! According to the overall study group, the recipients of immunoglobulin replacement therapy who had been hospitalized for severe infection last month showed a higher mortality rate of 30 days per person compared to those without infections (0.090 versus 0.008, respectively)-respectively)-respectively)-respectively).

Despite the increasing use of immunoglobulin replacement therapy during the study period, the rate of serious infections that require hospitalization increased from 1.9% to 3.9%. The researchers also noted that, among patients receiving regular immunoglobulins, there was a significantly higher incidence of infection, while in the treatment of immunoglobulin replacement compared to non -treatment periods (0.056 versus 0.038 infections per person, respectively). Among patients in regular immunoglobulins, 46.9% remained in treatment from one to five years and 23.5% received immunoglobulins for more than five years, under conditions for monitoring and survival.

“Not only did we not see a decrease in infection or hospitalizations among patients receiving immunoglobulins, we found that many were in this treatment for prolonged periods,” said Dr. Wood. “It is important to evaluate how long these patients remain in treatment and why to avoid unnecessary, prolonged and expensive treatment of a product on a limited offer internationally.”

Immunoglobulins are usually administered intravenously in a hospital environment, although subcutaneous infusions at home are increasing in popularity. The high cost of treatment is largely driven by the complex construction process and is aggravated by the frequency of treatment. For patients with CLL, intravenous immunoglobulins are generally administered on a monthly basis. In Australia, where this study was carried out, the cost of immunoglobulin is fully subsidized by the government, but in the United States and other countries, economic burden may be important.

“The cost of this treatment. Its weight for patients and the patterns of use and infection we have observed are a clear appeal for better instructions on the use of immunoglobulins,” said Carrillo. “Although there are criteria for access to government -funded treatment in this population in Australia, clear clinical guidelines are missing.”

The study has some limitations, given its retrospective nature, that is, the potential bias and incomplete data, especially around clinical prognostic factors, the severity of the disease and the treatment of cancer. In addition, there were significant differences at the start between the comparative groups of patients, in particular those who did and did not receive immunoglobulins and those who received it regularly for intermittent.

Researchers currently have ongoing surveillance studies, including a clinical test that compares immunoglobulins and antibiotics to prevent infections in CLL patients, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma and studies that examine the cost of immunoglobulins.

Source:

Magazine report:

De albornoz, sc, et al. (2025) Use of immunoglobulin, survival and infection in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The blood progresses. doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvans.2025015867.