Wendy Ouriel

Chicken is by far the worst thing you can put in your body.

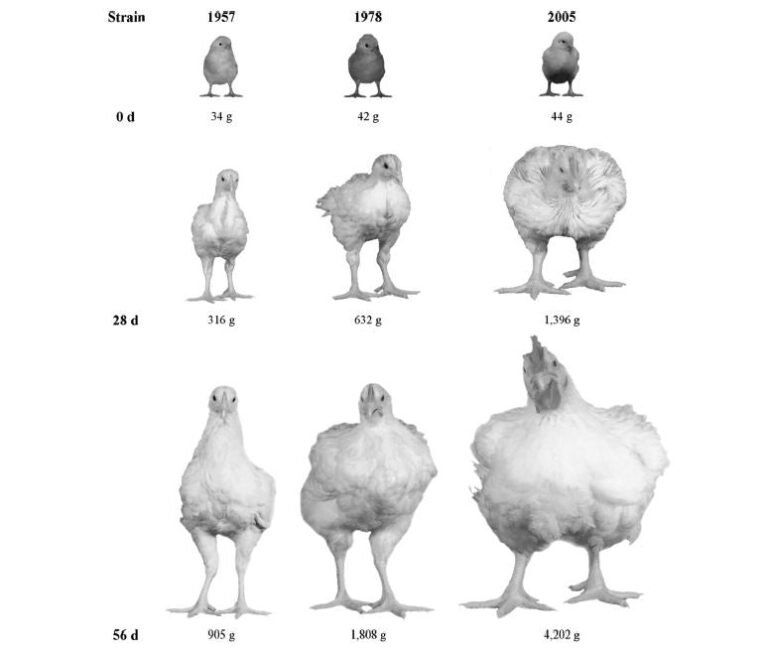

A chicken today does not look like what a chicken looked like 50 years ago. Through selective breeding, injections of pharmaceutical chemicals, and hormone manipulation, chickens are engineered to grow bigger and faster, producing more meat to meet consumer demand. These changes have altered the genetic makeup of chickens to the point where they look nothing like what they once were, even just a century ago.

The reason why chickens look different is because of artificial breeding and injection of medicinal chemical. Research published in Poultry Science found that today’s broilers are bred to reach market weight up to three times faster than chickens in the 1950s, primarily through selective breeding focused on muscle growth (Havenstein et al., 2003). In addition, the Journal of Animal Science highlights that modern poultry production often involves the administration of antibiotics and hormones to enhance growth rates and manage disease in crowded farms (Chapman & Johnson, 2002). These methods not only affect the size and growth rate of chickens, but have fundamentally changed their genetics and physiology, resulting in chickens that don’t even look like chickens anymore, but genetically mutated.

Chicken is, in my opinion, the worst thing you can eat because of how adulterated it has become. Compared to many other animals raised for food, chickens have probably undergone the most extreme changes. Through constant exposure to growth hormones, antibiotics and selective breeding, chickens today are fundamentally different from their ancestors. The cumulative impact of these changes has resulted in what is essentially a laboratory creation – a “mutated” animal whose makeup is no longer natural. When you eat this highly modified organism, you consume not only the meat but also the leftover chemicals and hormones used in its production. This, I believe, contributes to widespread health problems as our bodies are exposed to compounds that were simply not present in the chickens of the past.

And before anyone wants to join in with the “but I eat organic chicken,” chickens, whether from organic or conventional sources, are exposed to chemicals, including antibiotics, growth-promoting agents, and environmental pollutants. Research in Environmental Health Perspectives (2020) found that even “organic” chickens can contain residues of chemicals such as arsenic and persistent organic pollutants (POPs), possibly from soil contamination or environmental exposure during production (Trasande et al., 2020 ). Additionally, a reference to Frontiers in Public Health (2021) highlights the continued presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in organic poultry due to cross-contamination from neighboring conventional farms (Rothrock et al., 2021). These chemicals, many of which act as endocrine disruptors, accumulate in human tissues over time, contributing to inflammation, hormonal imbalance, and general decline in health.

I don’t understand how you can eat something so bad and be ok health wise. And the problem is that people who eat chicken don’t eat it once or twice a year, they eat it once or twice a day. This means that your body will never get rid of the chemicals you put into it, and that you are feeding yourself a mutated organism and slowly mutating yourself in the process.

Chicken skin

The features I see in women who eat chicken are always the same to the point where I pretty much hit 1000 recognizing it. I don’t see this the same as any other diet, whether it’s a red meat diet, pure vegetarian or whatever. It is only when the person eats chicken several times a week.

1. A pale skin color

2. Yeasted look on the skin

3. Pulled, drawn look to the skin, even in younger people

4. Dryness, or simply lack of skin hydration in appearance

5. Lack of redness in the skin which means reduced blood flow

What you eat is why you will get cancer

In addition to contributing to less glowing skin, I believe that eating chicken may play a role in the development of breast cancer. Through my studies in cancer biology, one thing was clear: very few cancers are purely genetic. Many people turn to genetics as the main cause of cancer, which can absolve personal responsibility for lifestyle factors that can significantly affect health outcomes. However, the scientific consensus aligns with the idea that while genetics may predispose, it rarely predetermines cancer. For example, research published in Reviews of nature Cancer (2015) estimated that only about 5–10% of cancers are due to inherited genetic mutations (Anand et al., 2008). Even with a mutation like BRCA1 or BRCA2, environmental and lifestyle factors greatly influence cancer development.

Studies show that diet plays an important role. For example, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (2013) found that higher consumption of processed meats, often associated with modern diets, was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (Etemadi et al., 2013). Furthermore, cross-cultural studies reveal that breast cancer rates are significantly lower in countries where the diet is predominantly plant-based and low in processed animal products, particularly in many Asian countries, compared to Western countries such as the USA (Wu et al., 2015 ). The link between high body weight, often exacerbated by a high intake of animal protein, and breast cancer is also well documented, as body fat can affect estrogen levels, which are linked to breast cancer risk.

Although many would like to believe otherwise, genetic mutations may be a factor in cancer, but they do not make cancer inevitable. Environmental and dietary choices are likely far more important, and frequent consumption of modern chicken—laden with growth hormones and chemicals—may contribute to cancer risk, especially when combined with other lifestyle factors.

I don’t think there is anything morally wrong with eating meat. I think if you wanted to go out into the woods, hunt a deer and eat it, then that’s your right. An animal was in its natural habitat, living a natural life that was quickly ended to preserve the life of another animal. When I was in Africa, I ate chicken because it was in a nice coop one minute, and then its head chopped off the next. It tasted completely different than any chicken I’ve had even in the States. It was a real animal that I ate and not an industrially produced lab creation.

However, there is something morally wrong with injecting an animal with pharmaceutical chemicals, mutating it until it can barely stand, confining it to a filthy cage too small to move, and forcing it to live a life so dark whose only distraction is chewing. His prison closes until his beak wears out.

I would not eat this animal, because supporting this kind of practice is wrong. And I believe that the diseases people develop from supporting this industry may be nature’s way of balancing the scales – a “you harm me, I harm you” message from the earth.

Eating meat should be done rarely and humanely. If not for the sake of the animals, then at least for yourself, so that you can have good skin and a healthier body.

References

Havenstein, GB, Ferket, PR, & Qureshi, MA (2003). Growth, viability and feed conversion of broiler chickens in 1957 versus 2001 when representative of the Fed Broiler diets 1957 and 2001. Poultry Science, 82(10), 1500–1508. doi:10.1093/ps/82.10.1500.

Chapman, HD, & Johnson, ZB (2002). Use of antibiotics and probiotics in poultry production: A review. Journal of Animal Science, 80(E-Suppl_1), E12-E16. doi:10.2527/animalsci2002.0021881200800ES0003x.

Trasande, L., Shaffer, RM, Sathyanarayana, S. (2020). Food Additives and Children’s Health: Chemical Residues in Food. Environmental Health Perspectives, 128(8), 086001. doi:10.1289/EHP6404.

Rothrock, MJ, et al. (2021). Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in organic and conventional poultry production. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 559956. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.559956.

Anand, P., Kunnumakkara, AB, Sundaram, C., et al. (2008). Cancer is a preventable disease that requires significant lifestyle changes. Nature Reviews Cancer, 8, 243–252. doi:10.1038/nrc2323.

Etemadi, A., et al. (2013). Meat consumption and risk of mortality and cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 105(14), 1105–1114. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt147.

Wu, AH, Ziegler, RG, Horn-Ross, PL, et al. (2015). Asian American dietary patterns and breast cancer risk. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 102(6), 1380–1390. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.110239.