A national study shows that relocation to a more wandering city leads to continuous increases in daily steps and moderate to intense exercise, emphasizing urban design as a powerful lever for better public health.

Study: Physical Experiment links across the country, built environment with physical activity. Credit Picture: Jaromir Chalabala / Shutterstock

In a recent article in the magazine NatureResearchers at the University of Washington, Stanford University and collaborators studied how changes in the ease of structured environments affect physical activity, using data from people in all the United States.

They found that the transition to more wandering cities increased the number of steps walking people every day. These profits lasted at least three months and proved to most aged and sex groups, although the increase was not statistically significant for women over 50.

Background

Natural inactivity is widespread worldwide. It contributes to significant non -contagious diseases, including cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. By 2050, rapid urbanization will mean that most people live in cities, so urban design will become even more important for public health.

While previous research has explored links between the constructed environment, especially the walk and the physical activity, the findings were inconsistent. A basic uncertainty is whether the highest levels of activity are driven by the environment or simply reflect personal preferences for active living.

Many previous studies have encountered restrictions, including small sample sizes, limited geographical coverage, the use of self -determined information that can be biased, cross -sectional studies that impede causal conclusions and confusing the self -selection of self -selection.

To overcome these challenges, researchers can now use smartphones to constantly and objectively record both position and physical activity, allowing large real world analyzes. These data can reveal wide standards in health behavior, urban mobility and the spread of the disease and also expose differences between physical activity measures based on self -reporting.

For the study

The authors used a huge set of data derived from the smartphone to separate the environmental impacts from individual preferences, quantifying how changes in walking capacity affect physical activity both in the population and individual levels.

The research team analyzed almost 250,000 days of data from 5,424 US users of a smartphone application (identified by a base set of over 2.1 million US users) that moved at least once more than three years, resulting in 7,447 moves among more than 1,600 cities.

Step measurements were constantly recorded through smartphone accelerators, which have been validated for accuracy in both laboratory and real arrangements. Physical activity was measured for up to three months before and after each movement, creating a large large -scale experiment to assess the impact of changes in the built -in environment.

Participants represented a series of body mass categories (BMI), age and sex. Most of the short -term trips were excluded and sensitivity tests confirmed that the results were strong in different definitions of relocation. The possibility of walking was quantified using the foot score. The analysis included statistical tests (two -sided t tests) and agglomerated results in all relocations.

To tackle the possible selection bias, the study compared movements with cities with similar ability and did not find significant activity changes, arguing the view that the observed differences were due to environmental factors and not to personal preferences. The relationship between changes in the possibility of walking and physical activity was also symmetrical, with reductions in the loss of activities that produces precisely similar size to increases. The set of data also allowed subgroups by age, gender, BMI and basic level of activity.

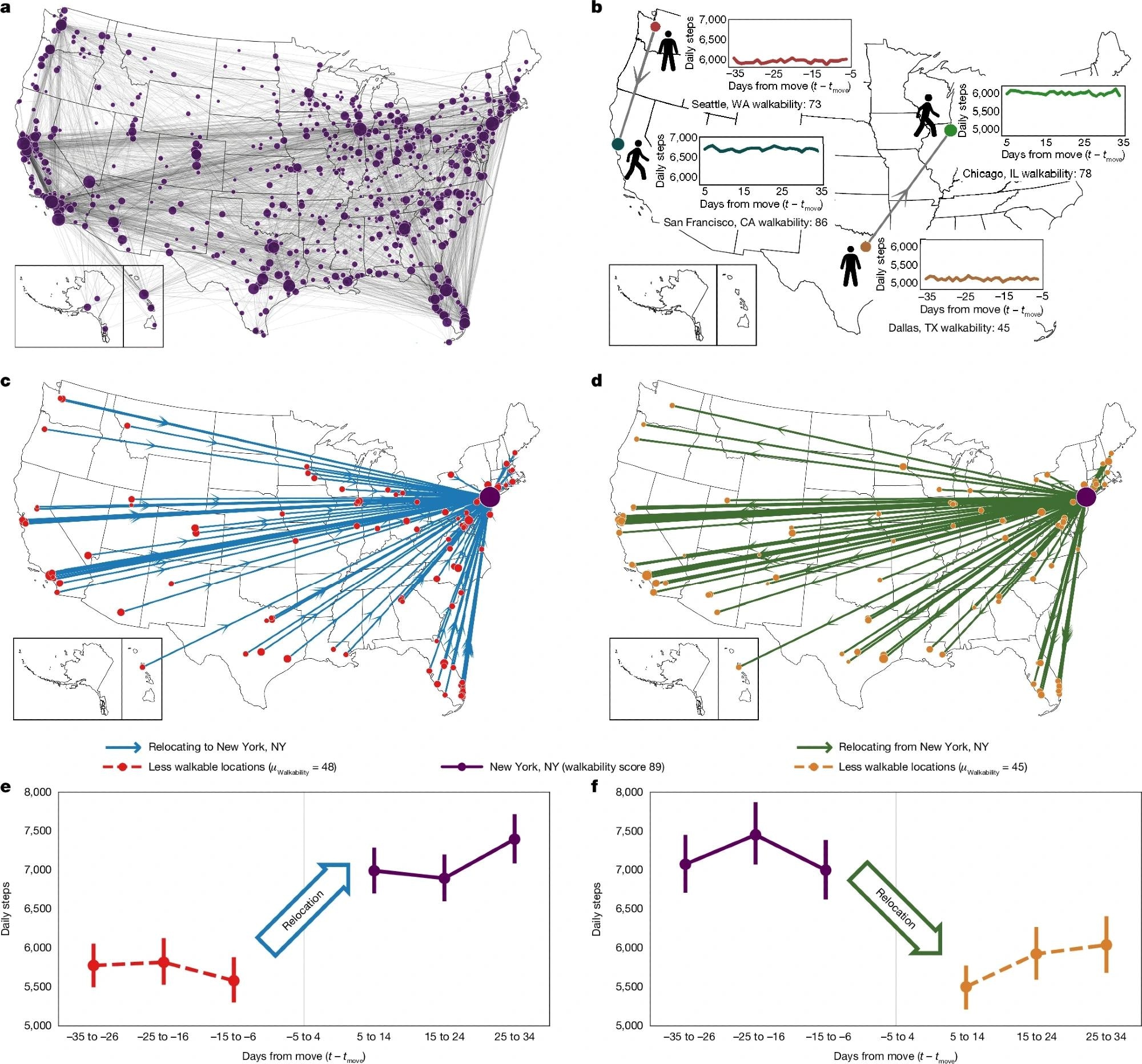

aDuring the observation period, 5,424 participants carried 7,447 times among 1,609 US cities. The area of the circle is proportional to the square root of the number of relocations to and from the city. siParticipants’ physical activity levels were attended through smartphone acceleration for several months before and after relocation, creating a study across the country of 7,447 quasi -authorization. do–tPhysical activity of participants moving from fewer locations in New York (do;MI), compared to participants moving in the opposite direction (d;t). Activity levels change significantly immediately after relocation and are symmetrically but reversed for participants moving in the opposite direction (MI;t). All error rods in all items correspond to 95%confidence intervals. Credits: a–dMaps reproduced by US Inventory Office (https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/2016/geo/carto-boundary-file.html) siwalking human silhouette reproduced by Wikimedia Commons under a creative commons CC by 1.0 permission.

aDuring the observation period, 5,424 participants carried 7,447 times among 1,609 US cities. The area of the circle is proportional to the square root of the number of relocations to and from the city. siParticipants’ physical activity levels were attended through smartphone acceleration for several months before and after relocation, creating a study across the country of 7,447 quasi -authorization. do–tPhysical activity of participants moving from fewer locations in New York (do;MI), compared to participants moving in the opposite direction (d;t). Activity levels change significantly immediately after relocation and are symmetrically but reversed for participants moving in the opposite direction (MI;t). All error rods in all items correspond to 95%confidence intervals. Credits: a–dMaps reproduced by US Inventory Office (https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/2016/geo/carto-boundary-file.html) siwalking human silhouette reproduced by Wikimedia Commons under a creative commons CC by 1.0 permission.

Basic findings

The relocation to more wandering cities has increased daily steps, while moving to less wandering areas that produced equivalent reductions. For example, moving from the 25th to the 75th percentage of the seizure potential increased the activity by about 1,100 steps per day (about 11 additional minutes), with changes that are maintained for at least three months.

The results were consistent in seasons, scale and levels of income, and inventory data showed that most movements were for family, work or housing, not for walking, reducing self -employee concerns.

The increases in the steps was largely due to a profit in moderate to intense physical activity (MVPA), defined in this study as an activity at a rate of at least 100 steps per minute, especially hasty walking, with great improvements (49-80 points), adding about 1 hour MVPA per week. An equivalent MVPA loss appeared for similar reductions in Walkability. This almost doubled the percentage of participants who meet the US aerobic guidelines (from 21.5% to 42.5%), a basic percentage lower than standard estimates of self -reported ones, reflecting well -known divergences between objective and self -reported measures.

The results were observed at levels of age, sex, BMI and base, although elderly women showed less profits and did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that additional interventions may be needed.

Simulation models estimate that increasing all US positions at Chicago/Philadelphia’s Walkability level could lead to 36 million more Americans to respond to activity guidelines, while New York levels could increase this by 47 million. These simulations were adapted to age differences between the smartphone sample and the US adult population.

These results highlight the improvements of Walkability as a gradual strategy for enhancing physical activity at the population level.

Conclusions

The advantages of this analysis include the large, different set of data, the timeless design, the objective steps measurement and the consistency of the findings in climates, seasons, income levels and demographic groups.

The results relate to the common restrictions on the previous research, such as small samples, the dependence on the data mentioned by the self -reported and the inability to control self -control. The evidence against self-selection of housing are reinforced, but do not prove the causal interpretation.

However, the restrictions of this study include possible bias towards the highest socio -economic situation and participants in consciousness of health, the restriction of US cities, and the dependence on city level ratings, which hide the fluctuations of neighboring levels and the specific characteristics of the specific levels.

The method also loses non -steps -based activities and requires participants to transfer their phones to conceive of data. However, the growing prevalence of smartphones and mobile devices should reduce such prejudices over time.

The findings have strong political consequences, suggesting that improving the route could significantly enhance physical activity at the population level, complementing interventions focused on individual.

While achieving the possibility of wandering cities everywhere is unrealistic, targeted changes in urban planning could bring significant health benefits, especially if in combination with age and gender -specific strategies for groups such as older women, who may face additional obstacles.