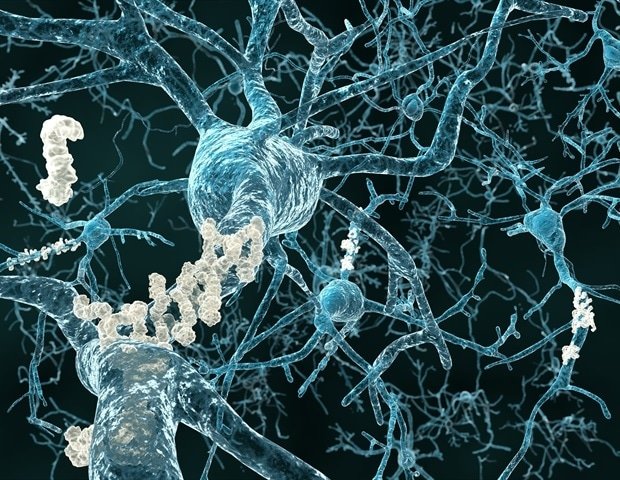

Age-related memory decline and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s are often considered irreversible. But the brain is not static. Neurons are constantly adjusting the strength of their connections, a property called “synaptic plasticity,” and this flexibility is the basis of memory and learning.

But aging and Alzheimer’s disrupt many cellular processes that support synaptic plasticity. A key question is whether and how affected cells can be helped to maintain their plasticity.

Memories are thought to be based on sparse groups of neurons called ‘engrams’, which are activated during learning and reactivated during recall, forming part of the brain’s ‘memory trace’. In aged brains and animal models of Alzheimer’s disease, engrams may malfunction and memory recall suffers.

A team led by Johannes Gräff at EPFL’s Brain Mind Institute asked whether revitalizing these engram neurons could restore memory after the decline has already begun? In a study published in Neuronthe team reports that “partial reprogramming” of engram neurons restores memory performance across multiple mouse settings. The approach uses a short, controlled pulse of three genes, Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4 collectively referred to as “OSK”.

Previous studies have shown that carefully timed expression of these factors can restore several aging-related features in cells. Here, the team targeted OSK specifically to the literacy neurons that are active during learning, rather than broadly across the entire brain.

Tagging and OSK control

Working in mice, the researchers used gene therapy vectors (adenogenesis-associated viruses) delivered by precise injections into the brain. They combined two components: a system that adds a fluorescent label to neurons activated by learning, and a switch that briefly activates OSK during a set time window.

The team used their approach in brain regions known to support different kinds of memory: the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, which is important for learning and recent recall, and the medial prefrontal cortex, which contributes to remote recall two weeks later.

Back to a newer state

In aged mice, brief activation of OSK in hippocampal engram neurons associated with learning restored memory, essentially restoring performance to levels seen in young controls. When the same approach was applied to prefrontal cortex engrams, it also retrieved remote memories formed weeks earlier.

The reprogrammed neurons also showed signs of improved health. They retained their neuronal identity and displayed molecular features associated with a younger state, including changes in nuclear structure associated with aging.

Next, the team looked at mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. In a spatial learning task, the mice exhibited inefficient navigation and impaired memory strategies. Reprogramming the dentate gyrus engrams improved learning strategies during training, while targeting the prefrontal engrams restored long-term spatial memory.

Further analysis revealed that Alzheimer’s disease-related changes in gene activity and neuronal firing within engram cells were partially reversed by OSK activation.

A proof of concept

The study is a proof of concept for restoring function to a specific group of memory-related neurons to improve memory performance, even after the onset of cognitive decline. By limiting OSK expression to a small number of neurons and a short period of time, the approach captures beneficial effects while reducing the risk of disrupting cell functions.

Source:

Journal Reference: