A large multicenter clinical trial led by King’s College London with 150 children and adolescents has shown that a device approved by the US FDA to treat ADHD is not effective in reducing symptoms.

The device – which uses an approach called trigeminal nerve stimulation (TNS) – was approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat ADHD in 2019 based on a small study. These new findings from a larger multicenter trial, published in the journal Nature Medicine, suggest that authorities should reconsider the original evidence that supported the FDA’s approval. Notably, TNS is not currently recommended for use in the UK by NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines.

The trial was conducted in collaboration with the University of Southampton and funded by the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Programme, a collaboration between the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the UKRI Medical Research Council (MRC), with further support from the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) affects 5 to 8 percent of school-age children worldwide and is associated with age-inappropriate problems with attention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity that can impair daily functioning.

Stimulant drugs improve symptoms in 70 percent of those who take them in the short term, but there is less evidence of their long-term effects.

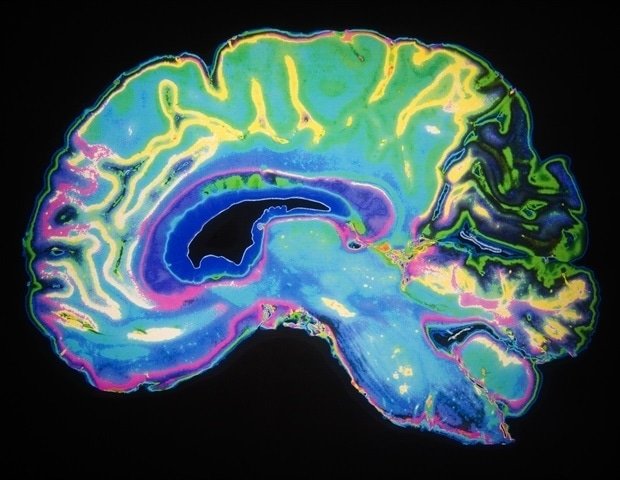

To provide an alternative to medication, researchers have developed and tested approaches that use non-invasive brain stimulation, working on the areas identified as affecting ADHD.

One of these approaches involves trigeminal nerve stimulation (TNS), targeting a branch of this facial nerve that is thought to activate the brainstem and from there other areas of the brain that may be related to ADHD, particularly the geniculate locus, which plays a role in arousal that is typically reduced in people with ADHD. TNS is thought to stimulate other attention-related brain regions such as frontal and thalamic regions via the brainstem in a bottom-up manner.

A previous small trial in the US with 62 children diagnosed with ADHD showed that when TNS is applied every night for eight hours for a month, it is effective in reducing symptoms – this research led to its FDA clearance for use in the US. However, the control condition did not involve stimulation and blinding was not tested after one month, raising questions about a potential placebo effect.

This new UK clinical trial at two sites in London and Southampton tested TNS in a wider range of 150 children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD between the ages of eight and 18 and applied a more stringent placebo condition. Half the sample received real TNS for about 9 hours each night for four weeks via battery-powered electrodes applied to the forehead. The other half of the sample received the “sham” condition where the electrodes were still applied to the forehead every night for four weeks, but the participants only received 30 seconds of stimulation every hour at a lower frequency and pulse width, which are believed to be ineffective and therefore act as a “control” condition.

Professor Katya Rubia, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN), King’s College London and senior author of the study said: “Our study shows how important it is to design an appropriate placebo condition in clinical trials of brain therapies. that they can accommodate brain differences associated with ADHD, so it is of utmost importance to control for placebo effects in modern brain treatments to avoid false hope.

This multicenter trial was designed to address key limitations of the previous pilot study that informed the FDA to clear TNS for ADHD, particularly using a tightly controlled sham condition that supported successful blinding during the treatment period. Unlike the previous study, which was limited to younger children, we also included adolescents, a clinically important group that received well-documented challenges with long-term medication adherence. These design choices allowed for a more robust and clinically relevant assessment of TNS.”

Dr. Aldo Conti, postdoctoral researcher at IoPPN and the Florence Nightingale School of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care, King’s College London and first author of the study

Comparing the groups, the researchers assessed the effectiveness of TNS by assessing parent-reported ADHD symptoms, along with other outcomes such as mind-wandering and attention, depression and anxiety, and sleep.

The trial showed that TNS was safe with no serious side effects, and most participants found it mild or no burden to use. However, results showed no significant change in ADHD symptoms, objective measures of hyperactivity, attention, and related mood and sleep behaviors.

Professor Samuele Cortese, NIHR Research Professor at the University of Southampton and study leader for the Southampton website, said: “Rigid evidence such as that generated by this study is essential to support shared decision-making about ADHD interventions. It empowers people with ADHD and their families to make informed choices about treating their ADHD and their families. What treatments work and what do not based on the best evidence’.

The trial was conducted by King’s Clinical Trials Unit and recruitment involved Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) clinics in the following NHS trusts: South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Hampshire and Isle of Wight Healthcare (previously known as SOLENT NHS-NHSW Central Trust, London-HSWasle, London) Foundation Trust and South-West London and St. George’s Mental Health NHS Trust.