Estrogen, the main female sex hormone, although it performs some functions in men, is involved in a myriad of processes, which is why the body changes so much during menopause. This is because estrogen regulates hundreds of genes. A study led by the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO) now shows how they do it, looking directly into the cell’s nucleus. The researchers discovered that estrogen’s action depends on a physical property of DNA: its ability to twist or supercoil.

“We discovered that the way the DNA molecule is coiled and unwound, its topology, is key for cells to respond to estrogen,” explains CNIO researcher Felipe Cortés, co-leader of the study, which is published in Advances in Science.

When estrogen arrives, enzymes called topoisomerases regulate DNA winding, thereby controlling the activation of genes necessary for the cell to respond to hormones.”

Felipe Cortés, DNA Topology and Breaks Team Leader, CNIO

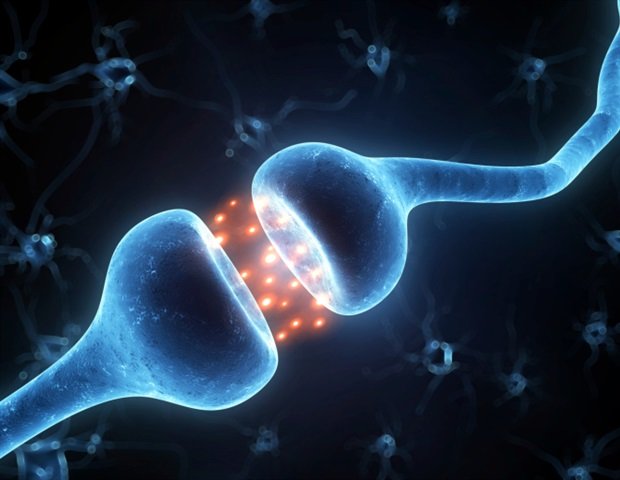

These are procedures that happen within minutes. Inside our cells, in the nucleus, the DNA molecule is constantly changing its conformation, twisting and unfolding to a greater or lesser degree, and this helps turn genes on or off.

The authors of the paper are now published at Advances in Science they include Gonzalo Millán-Zambrano from the Andalusian Center for Molecular Biology and Regenerative Medicine (CABIMER) at the University of Seville-CSIC-University Pablo de Olavide, and José Terrón Bautista, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Helmholtz Zentrum in Munich, Germany.

How to turn on the right gene at the right time

The genetic information encoded in each of our DNA – our genome – is made up of a sequence of different chemical components (usually represented as letters: A, T, C, G). The DNA sequence is the same in all cells of an organism, but each type of cell reads different parts of the DNA molecule – the genes – at different times, which is why different tissues and organs exist.

In other words, each cell carefully controls which genes it is reading – “turning on” or “expressing” – at any given moment. The question of how it does this is absolutely critical in biology, and is the focus of the newly published study.

One of the major paradigm shifts in this field comes from the recent realization that information in the genome is encoded in three dimensions. In other words, the 3D shape of the genome affects which genes are expressed at which time.

The third dimension of the genome

The nucleus of the cell, which is millimeters in diameter, houses our DNA, which, when unwound, is two meters long in the case of humans. DNA is therefore tightly folded, but not like tangled wires. follows a very strict command. This makes it possible for linearly distant regions of DNA to come into contact, and it is this physical proximity that turns genes on and off. The correct folding of DNA is so important that if there are mistakes, diseases can occur, including cancer.

Understanding this process is a rapidly evolving area of research. DNA folding determines how the cell reads and interprets the information in the genome. “We are beginning to understand how this three-dimensional organization affects gene activity,” Cortés points out.

Estrogen, gene activation and DNA supercoiling

Estrogens act as chemical signals that modify the expression of hundreds of genes related to reproduction, metabolism, cell growth, differentiation, and survival.

The new study in Advances in Science shows that this estrogen function is directly dependent on physical changes in DNA folding, changes caused by topoisomerase enzymes.

“We found that, in the presence of estrogen, topoisomerases modify DNA coiling, thereby controlling the activation of target genes,” explains Cortes.

Specifically, topoisomerases modify DNA supercoiling, the phenomenon by which the molecule twists on itself in the way that a cord from an old telephone cord, after a certain number of turns, spontaneously supercoils to relieve the natural twisting stress.

Supercoiling-regulating enzymes to control gene expression

“Changes in supercoiling caused by topoisomerases affect the three-dimensional organization of the genome and thus the way different regulatory regions touch each other; these contacts are necessary for the activation of estrogen-responsive genes,” says the researcher from the CNIO.

In short, “we showed that the way DNA twists is a previously overlooked layer of gene expression regulation. Until now, it was thought that topoisomerases simply removed DNA tensions. Our work shows that, in response to estrogen at least, the opposite happens: the cell actively creates and regulates these tensions to promote contacts that stimulate the activation of genes.”

Relationship to breast cancer

The study is related, although not directly, to the treatment of cancer. Many breast cancers need estrogen to grow, and standard treatments work by blocking this hormone signal. In addition, topoisomerase inhibitors, which directly affect DNA topology, are also used in the treatment of various tumors, sometimes in combination with hormonal therapies.

“Our results show that the way DNA is wrapped directly affects how cells respond to estrogen. This suggests that hormone signaling and topoisomerases, traditionally considered independent therapeutic targets, are functionally linked, which could explain mechanisms of resistance and contribute to the design of more personalized and effective therapies,” says Cortés.

Source:

Journal Reference: