Scientists have discovered two human gut microbes that produce serotonin, revealing how microbial chemistry can shape gut motility and nerve connectivity and opening up new possibilities for treating gut disorders like IBS.

In a recent study published in the journal Cell referencesresearchers identified human intestinal substances that decarboxylate 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) to produce serotonin.

Serotonin is an important signaling molecule in the gut, mediating gastrointestinal functions such as vasodilation, visceral sensitivity, and peristalsis. Abnormal serotonin signaling is involved IBS pathogenesis. The gut accounts for about 95% of the body’s serotonin pool. Mammalian enterochromaffin cells produce serotonin from tryptophan (Trp).

Studies have shown that the gut microbiota up-regulates the host’s production of serotonin Tph1 expression. Disrupting the gut microbiota with the use of antibiotics has been shown to shrink the colon Tph1 expression and serotonin levels. While serotonin has been detected in culture media of facultative anaerobes, incl Escherichia colithere is no evidence for microbial production of serotonin in the gut. However, in this study, microbial serotonin was derived from decarboxylation of 5-HTP and not from hydroxylation of Trp to 5-HTP.

The study and findings

The present study identified human gut bacteria that produce serotonin. First, the researchers compared serum and fecal serotonin levels Tph1– incomplete (Tph1-/-) and wild type (Tph1+/+) raised conventionally (CONV-R) and germ-free (GF) mice. Both serum and faecal serotonin levels were lower Tph1-/- relative to Tph1+/+ CONV-R mice. Tph1+/+ GF mice had lower serotonin levels than Tph1+/+ CONV-R mice.

While serum serotonin levels were not different from each other Tph1–/- CONV-R and GF mice, fecal serotonin levels were higher in Tph1–/- CONV-R mice than media GF counterparts. Further, Tph1–/- GF mice were conventionalized with caecal contents from Tph1+/+ CONV-R mice. This significantly increased faecal serotonin levels in conventional mice compared to Tph1–/- GF mice, indicating that the gut microbiota produces serotonin.

Microbial feces from six individuals were then cultured anaerobically and serotonin was quantified. Serotonin was produced in the growth medium, reaching maximum levels within the first 12 hours of inoculation. In addition, the researchers isolated bacteria from the feces of healthy people to identify the serotonin-producing strains. Several consortia containing at least one metabolizable species Trp were isolated and cultured.

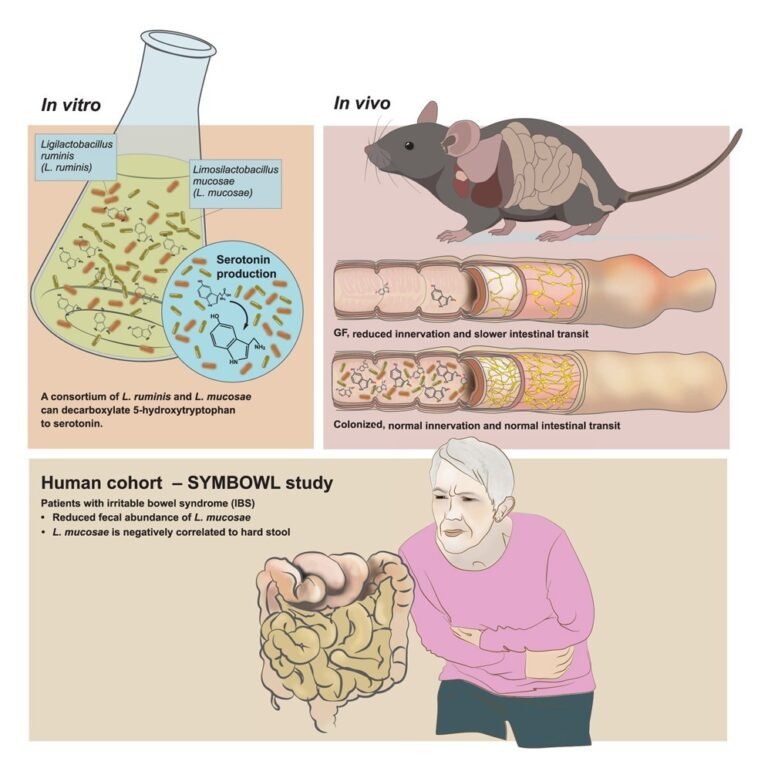

Only two consortia (Ls and h1L12h) synthesized detectable serotonin. Genomic analysis identified two species in Ls and seven in h1L12h. Limosilactobacillus mucosae and Ligilatobacillus ruminis were present in both Ls and h1L12h. Other consortia lacked one or both species. The team then investigated whether these two species produced serotonin in monocultures. These species were isolated as pure cultures in nutrient-rich broth.

However, no serotonin production was detected under aerobic or anaerobic conditions, suggesting that interactions between the two species may be required for serotonin synthesis. Consistent with this, serotonin and tryptamine production occurred in the co-isolated community and not in monocultures or simple cocultures in vitroalthough the reconstituted pair increased fecal serotonin in vivo. The study further confirmed that the L. mucosae strain encoded a tryptophan decarboxylase gene, which was cloned and functionally validated as capable of producing tryptamine from Trp and serotonin from 5-HTP.

Further experiments revealed that the two co-isolated lactobacilli produced tryptamine and serotonin in vitro by its decarboxylation Trp and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), respectively. Serotonin was not produced by Trp; 5-HTP was required. It was decarboxylated in vitro in microbial communities rather than monocultures.

The group was then colonized Tph1–/- GF mice with Ls, which increased faecal levels of tryptamine and serotonin and serotonin immunoreactivity in colonic tissue, but did not change serum serotonin levels, indicating a local rather than a systemic effect.

Monocolonization with L. mucosae or L. ruminis did not increase faecal serotonin, but colonization of reconstituted Ls increased faecal serotonin levels. Further, the researchers assessed whether Ls colonization affects colonic innervation and stained proximal colonic sections from GF and Ls-colonization Tph1-/- mice with Tuj1, a pan-neural marker. This showed an increased Tuj1-immunoreactive area in the Ls group relative to GF controls and increased serotonin immunoreactivity within the isolated myenteric plexus.

Further, the colonic myenteric plexus of the enteric nervous system was isolated and stained to visualize serotonin immunoreactive areas. This showed increased serotonin immunoreactivity in the myenteric plexus of Ls colonized Tph1-/- mice. The reconstituted Ls also increased the area of serotonin in the myenteric plexus, whereas the single strains did not. Next, the team investigated whether Ls colonization affects gut transit time.

Wild type GF Mice showed slower transit than wild-types CONV-R mice. However, wild-type Ls colonization GF mice normalized transit time to that of the wild type CONV-R mice. Colonization significantly increased faecal serotonin levels, which were positively correlated with intestinal transit rate. This association was significant overall and in women, but not in men, when analyzed separately. Notably, Ls colonization was not increased Tph1 expression in the proximal colon, suggesting Ls as a source of serotonin, and Mao expression was not reduced.

The researchers then determined the abundance of feces L. ruminis and L. mucosaefecal and serum serotonin levels, total oral transit time, and stool composition and form in 147 IBS patients and 27 healthy controls. They found no significant differences in serum and fecal serotonin levels between groups. IBS patients showed significantly lower abundance only L. mucosae rather than controls. Besides, L. mucosae abundance was negatively associated with hard stools IBS patients, reflecting a weak correlation (Spearman ρ ≈ -0.23, FDR = 0.044) according to the paper’s reported effect size.

conclusions

Overall, the findings showed that members of the human gut microbiota produce serotonin in cultures and in vivo. Co-isolated man L. ruminis and L. mucosae strains produce serotonin from 5-HTP in vitro and regulate intestinal serotonin levels, intestinal transit time, and enteric innervation in vivo. These results were obtained in germ-free mice. The mechanisms of microbial regulation of serotonin and the clinical implications in humans remain to be determined.

Restrictions: The mechanistic regulators of microbial serotonin synthesis have not been resolved. Effects were demonstrated in germ-free mice, but human serotonin levels did not differ by IBS situation. The study reports industry relations and a patent application.