By recruiting the immune system to fight cancer cells, immunotherapy has improved survival rates, offering hope to millions of cancer patients. However, only about one in five people respond positively to these treatments.

Aiming to understand and address the limitations of immunotherapy, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have discovered that the immune system can be its own worst enemy in the fight against cancer. In a new study in mice, a subset of immune cells — type 1 regulatory T cells, or Tr1 cells — did its normal job of preventing the immune system from overreacting, but did so while inadvertently limiting the cancer-fighting power of immunotherapy.

Tr1 cells were found to be a hitherto unrecognized barrier to the efficacy of immunotherapy against cancer. By removing or bypassing this barrier in mice, we successfully activated cancer-fighting immune cells and discovered an opportunity to extend the benefits of immunotherapy to more cancer patients.”

Robert D. Schreiber, PhD, Senior Study Author, Andrew M. and Jane M. Bursky Distinguished Professor, Department of Pathology and Immunology, and Director, Bursky Center for Human Immunology & Immunotherapy, Washington University School of Medicine

The study is available at Nature.

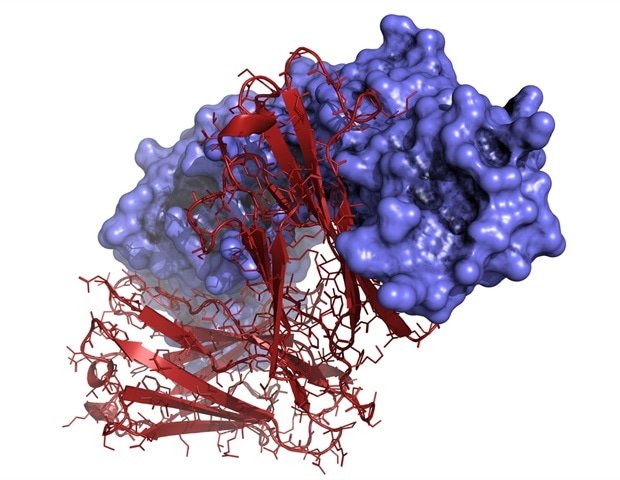

Cancer vaccines represent a new approach to personalizing cancer immunotherapy. By targeting mutated proteins specific to a patient’s tumor, such vaccines cause killer T cells to attack cancer cells while leaving healthy cells unharmed. Schreiber’s team had previously shown that the most effective vaccines also activate helper T cells, another type of immune cell, which recruit and expand additional killer T cells to destroy tumors. But when they tried adding increased amounts of the helper T cell target to supercharge the vaccine, they found they created a different type of T cell that inhibited rather than promoted tumor rejection.

“We tested the hypothesis that by increasing helper T cell activation we would cause enhanced eradication of sarcoma tumors in mice,” said first author Hussein Sultan, PhD, instructor of pathology and immunology. So, he injected groups of tumor-bearing mice with vaccines that equally activated killer T cells while causing different degrees of activation of helper T cells.

Much to the researchers’ surprise in this latest study, the vaccine intended to overactivate helper T cells produced the opposite effect and inhibited tumor rejection.

“We thought that more activation of helper T cells would optimize eradication of sarcoma tumors in mice,” Sultan said. “In contrast, we found that vaccines containing high doses of helper T cells induced inhibitory Tr1 cells that completely prevented tumor eradication. We know that Tr1 cells normally control an overactive immune system, but this is the first time they have been shown to reduce it in fighting cancer.”

Tr1 cells normally put the brakes on the immune system to prevent it from attacking healthy cells in the body. But their role in cancer has not been seriously investigated. Looking at previously published data, the researchers found that tumors from patients who had responded poorly to immunotherapy had more Tr1 cells compared to tumors from patients who had responded well. The number of Tr1 cells also increased in mice as the tumors grew, rendering the mice insensitive to immunotherapy.

To bypass the inhibitory cells, the researchers treated the vaccinated mice with a drug that boosts the fighting power of killer T cells. The drug, developed by biotech start-up Asher Biotherapeutics, carries modifications to an immune-boosting protein called interleukin 2 (IL-2) that specifically boosts killer T cells and reduces the toxicity of unmodified IL-2 therapies. The extra boost from the drug overcame the inhibition of the Tr1 cells and made the immunotherapy more effective.

“We are committed to personalizing immunotherapy and expanding its effectiveness,” said Schreiber. “Decades of basic tumor immunology research have expanded our understanding of how to activate the immune system to achieve the most potent anti-tumor response. This new study adds to our understanding of how to improve immunotherapy to benefit more people.”

As co-founder of Asher Biotherapeutics – which provided the mouse version of the modified IL-2 drugs – Schreiber is indirectly involved in the company’s clinical trials testing the human version of the drug as monotherapy in cancer patients. If successful, the drug has the potential to be tested in combination with cancer treatment vaccines.

Source:

Journal Reference:

Sultan, H., et al. (2024). Neoantigen cytotoxic Tr1 CD4 T cells suppress cancer immunotherapy. Nature. doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07752-y