Medical research has belittled women for decades. This is especially true for older women, leaving doctors without critically important information about how to best manage their health.

Late last year, the Biden administration promised to tackle this problem with a new effort called the White House Initiative for Research on Women’s Health. This prompts an intriguing question: What priorities should be on the initiative’s list when it comes to older women?

Stephanie Faubion, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health, launched into a critique when I asked about the current state of research on older women’s health. “It’s completely inadequate,” he told me.

One example: Many drugs widely prescribed to older adults, including statins for high cholesterol, were studied primarily in men, with the results extrapolating to women.

“It’s assumed that women’s biology doesn’t matter and that women who are premenopausal and those who are postmenopausal respond similarly,” Faubion said.

“This needs to stop: The FDA needs to require clinical trial data to be reported by gender and age to say whether drugs work the same, better or less well in women,” Faubion insisted.

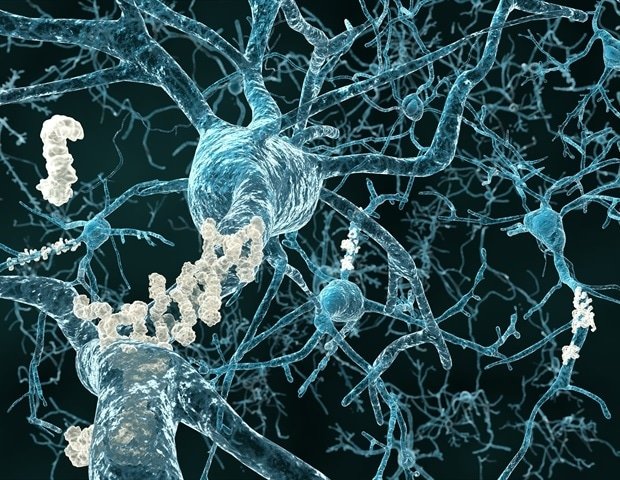

Consider the Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi, which was approved by the FDA last year after the manufacturer reported a 27 percent slower rate of cognitive decline in people who took the drug. A supplementary appendix to a Leqembi study published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that gender differences were significant – 12% slowing for women, compared to 43% for men – raising questions about the drug’s effectiveness for the women.

This is especially important because nearly two-thirds of older people with Alzheimer’s disease are women. Older women are also more likely than older men to have multiple medical conditions, disabilities, difficulty with daily activities, autoimmune diseases, depression and anxiety, uncontrolled high blood pressure and osteoarthritis, among others, according to dozens of research studies.

Still, women are resilient and outlive men by more than five years in the U.S. As people move into their 70s and 80s, women outnumber men by significant margins. If we are concerned about the health of the aging population, we must be concerned about the health of older women.

In terms of research priorities, here are some suggested by doctors and medical researchers:

Heart disease

Why do women with heart disease, which becomes much more common after menopause and kills more women than any other condition, receive less recommended care than men?

“We are particularly less aggressive in treating women,” said Martha Gulati, director of preventive cardiology and associate director of the Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center at Cedars-Sinai, a health system in Los Angeles. “We’re delaying assessments for chest pain. We’re not administering blood thinners at the same rate. We’re not doing procedures like aortic valve replacements as often. We’re not adequately treating hypertension.

“We need to understand why these biases in care exist and how to remove them.”

Gulati also noted that older women are less likely than their male peers to have obstructive coronary artery disease—blockages in large blood vessels—and more likely to have damage to smaller blood vessels that goes undetected. When they have procedures like heart catheterizations, women have more bleeding and complications.

What are the best treatments for older women because of these problems? “We have very limited data. That needs to be focused on,” Gulati said.

Brain health

How can women reduce their risk of cognitive decline and dementia as they age?

“This is an area where we really need to have clear messages for women and effective interventions that are feasible and accessible,” said JoAnn Manson, chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and principal investigator for Women’s. Health Initiative, the largest study of women’s health in the US

Many factors affect women’s brain health, including stress—dealing with sexism, caregiving responsibilities and financial pressure—which can fuel inflammation. Women experience a loss of estrogen, a hormone important for brain health, with menopause. They also have a higher incidence of conditions with serious effects on the brain, such as multiple sclerosis and stroke.

“Alzheimer’s disease doesn’t just start at age 75 or 80,” said Jillian Einstein, the Wilfred and Joyce Posluns Chair in Women’s Brain Health and Aging at the University of Toronto. “Let’s take a life course approach and try to understand how what happens earlier in women’s lives predisposes them to Alzheimer’s.”

Mental health

What explains older women’s greater vulnerability to anxiety and depression?

Studies point to a variety of factors, including hormonal changes and the cumulative effect of stress. In the journal Nature Aging, Paula Rochon, professor of geriatrics at the University of Toronto, also blamed “gender ageism,” an unfortunate combination of aging and sexism, that makes older women “largely invisible,” in an interview with Nature Aging .

Helen Lavretsky, professor of psychiatry at UCLA and past president of the American Geriatric Psychiatric Association, suggests several issues that need further investigation. How does the transition to menopause affect mood and stress-related disorders? What non-pharmacological interventions can promote psychological resilience in older women and help them recover from stress and trauma? (Think yoga, meditation, music therapy, tai chi, hypnotherapy, and other possibilities.) What combination of interventions is likely to be most effective?

Cancer

How can screening recommendations and cancer treatments for older women be improved?

Supriya Gupta Mohile, director of the Geriatric Oncology Research Group at the Wilmot Cancer Institute at the University of Rochester, wants better guidance on breast cancer screening for older women, broken down by health status. Currently, women 75 and older are concentrated, even though some are extremely healthy and others are particularly frail.

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force noted that “current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening mammography in women age 75 and older,” leaving doctors without clear guidance. “Right now, I think we’re under-screening fit older women and over-screening frail older women,” Mohile said.

The doctor also wants more research into effective and safe treatments for lung cancer in older women, many of whom have multiple medical conditions and functional impairments. The age-sensitive condition kills more women than breast cancer.

“For this population, decisions about who can tolerate treatment based on health status and whether there are gender differences in tolerability for older men and women need research,” Mohile said.

Bone health, functional health and frailty

How can older women maintain mobility and maintain their ability to care for themselves?

Osteoporosis, which causes bones to become weak and brittle, is more common in older women than older men, increasing the risk of dangerous fractures and falls. Once again, the loss of estrogen with menopause is to blame.

“This is extremely important for the quality of life and longevity of older women, but it is a neglected area that has not been well studied,” said Manson of Brigham and Women’s.

Jane Cauley, a distinguished professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health who studies bone health, would like to see more data on osteoporosis among older black, Asian and Hispanic women, who are undertreated for the condition. . He would also like to see better drugs with fewer side effects.

Marcia Stefanick, a professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine, wants to know what strategies are most likely to motivate older women to be physically active. And she would like more studies investigating how older women can better maintain muscle mass, strength and the ability to care for themselves.

“Impotence is one of the biggest problems for older women and it is essential to learn what can be done to prevent it,” she said.

|

This article was reprinted by khn.orga national newsroom that produces in-depth health journalism and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.

|