Despite decades of research, the mechanisms behind the quick flashes of insight that change the way a person perceives their world, called “one-shot learning,” have remained unknown. A mysterious type of one-shot learning is perceptual learning, in which seeing something once dramatically changes our ability to recognize it again.

A new study, led by researchers at NYU Langone Health, looks at the moments when we first recognize a blurry object, a primary ability that allowed our ancestors to avoid threats.

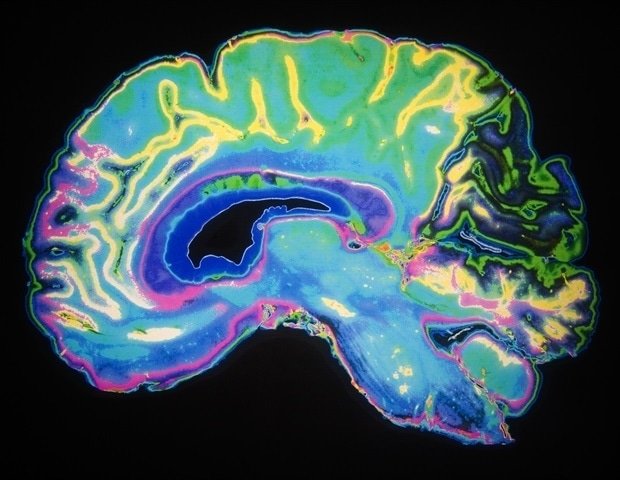

Posted online at Nature communicationsthe new work identifies for the first time the region of the brain called the high-level visual cortex (HLVC) as the place where “priors”—images seen in the past and then stored—are accessed to enable one-shot perceptual learning.

“Our work revealed, not only where the antecedents are stored, but also the brain computations involved,” said study co-senior author Biyu J. He, PhD, associate professor in the Departments of Neurology, Neuroscience, and Radiology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Importantly, previous studies have shown that patients with schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease have abnormal one-shot learning, such that previously stored priorities overwhelm what a person is currently looking at to create hallucinations.

“This study has provided a directly testable theory of how the precursors act during hallucinations, and we are now investigating the relevant brain mechanisms in patients with neurological disorders to reveal what is going wrong,” added Dr.

The research team is also looking at possible connections between the brain mechanisms behind visual perception and the more familiar type of “aha moment” when we understand a new idea.

Sharper image

For the study, the team of Dr. He’s investigated changes in brain activity caused when people are shown Mooney pictures – faded pictures of animals and objects. Specifically, study participants are shown blurry images of the same object and then a clear version. In the study of Dr. He’s in 2018 of this procedure, after seeing the clean version (and experiencing one-shot learning), subjects became twice as good at image recognition because the experiment forced them to use their stored preferences.

The researchers “took pictures” of brain activity during the previous access using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures the activity of brain cells by monitoring blood flow to active cells. Signaling strength along neural pathways (plasticity), however, is fine-tuned at the structural spaces (synapses) between brain cells, and fMRI can only measure activity within cells.

For this reason, the researchers combined fMRI with behavioral tests using Mooney images, electroencephalography (EEG) brain recordings, and a model based on machine learning—a form of artificial intelligence (AI)—to identify antecedents in HLVC.

To find the seat of one-shot perceptual learning, the research team first determined what kind of information is encoded in the signaling changes as prior access improves image recognition. To do this, the team changed the size of the images, their position on the page and their orientation (by rotating them) and recorded the effect of each change on image recognition rates. This behavioral study revealed that changes in image size did not alter single-shot learning, whereas rotating an image or changing its position partially reduced learning. The results suggested that perceptual priors encode prior patterns but not more abstract concepts (e.g., the breed of a dog in a picture).

The team then built statistical models that recorded patterns of brain cell activity via fMRI during prior access and found that only known patterns of neural coding in the high-level visual cortex matched the properties of the priors revealed by the behavioral study. The authors also investigated the temporal properties of activity changes using intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) by asking patients already undergoing iEEG monitoring during neurosurgical treatment to perform a brief perceptual task. iEEG collects signals from electrodes in brain tissue to measure rapidly changing signaling patterns that fMRI cannot measure. HLVC showed the first changes in neural signaling strength, just as earlier guided object recognition did.

As a final step, the research team built a vision transformer — an artificial intelligence model that finds patterns in image parts and fills in what’s missing based on probabilities. Just as HLVC was found to add prior weight to information coming from the eyes, the AI model stored accumulated image information (priors) in one unit and then used the stored data to better recognize incoming imaging data in another unit. After being trained on several images, the neural network model achieved one-shot learning ability similar to that seen in humans and better than other leading AI models without a comparable prior module.

“Although artificial intelligence has made great strides in object recognition over the past decade, no tool has yet been able to learn once like humans,” added co-senior author Eric K. Oermann, MD, assistant professor in the Departments of Neurosurgery and Radiology at NYU Langone. “We now expect the development of AI models with human-like perceptual mechanisms that classify new objects or learn new tasks with few or no training examples. This is further evidence of a growing convergence between computational neuroscience and the advancement of artificial intelligence.”

Together with Dr. He and Dr. Oermann, the authors included first authors Ayaka Hachisuka and Jonathan Shor, at the NYU Langone Institute for Translational Neuroscience, and first author Xujin Chris Liu of the NYU Tandon School of Engineering. Other authors from NYU Langone are Daniel Friedman, MD; Patricia C. Dugan, MD; and Orrin Devinsky, MD; in the Department of Neurology and Werner Doyle, MD, in the Department of Neurosurgery. Author Yao Wang is in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering. Authors from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai are Ignacio Saez in the Department of Neurosciences and Fedor Panov in the Department of Neurosurgery.

This work was supported by a WM Keck Foundation Medical Research Grant, National Science Foundation grant BCS-1926780, and NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Dr. Oermann owns equity in Artisight, Delvi and Eikon Therapeutics and has consulting agreements with Google and Sofinnova Partners. These relationships are managed in accordance with NYU policies.