For a while, walking the dog felt dangerous.

Earl Vickers was accustomed to taking Molly, the Shepherd-Boxer-Somening-Else mixture, for walks on the beach or around his neighborhood in the California Sea. A few years ago, however, he began to have problems remaining upright.

“If another dog came to us, I will end up on the ground every time,” Vickers, 69, a retired electrical engineer. “It looked like falling every other month. He was a bit crazy.”

Most of these falls did not do serious damage, though once fell backwards and hit his head on a wall behind him. “I don’t think I had a concussion, but it’s not something I want to do every day,” Vickers said, strongly. Once again, trying to break a fall, he broke two bones in his left hand.

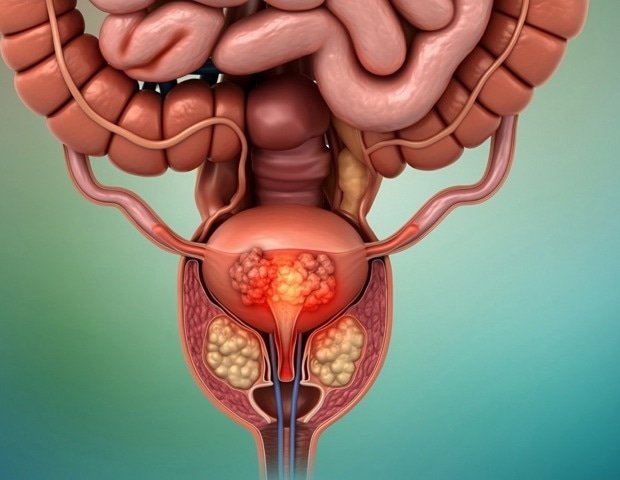

Thus, in 2022, he told the oncologist who had treated him for prostate cancer that he wanted to stop the cancer drug he had taken, away and up, for four years: Enzalutamide (sold as Xtandi).

Among the side effects mentioned by drugs are higher rates of falls and fractures between patients who took it, compared to those who received placebo. His doctor agreed that he could stop the drug and “I haven’t passed since then,” Vickers said.

Public Health experts have warned of the dangers of falls for the elderly for decades. In 2023, the latest year of data from the Disease Control and Prevention Centers, more than 41,000 Americans over 65 died of falls, an opinion article in Jama Health Forum pointed out last month.

More impressive than this figure, however, was another statistics: the autumn -related mortality among older adults has climbed sharply.

The author, Thomas Farley, an epidemiologist, said that the mortality rates of fall injuries among Americans over 65 have tripled over the last 30 years. Among them over 85 years, the higher risk group, falling rates of falls increased to 339 per 100,000 in 2023, from 92 per 100,000 in 1990.

The culprit, in his view, is the dependence of Americans on prescription drugs.

“Elderly adults are very medicinal, increasingly and with medicines that are inappropriate for the elderly,” Farley said in an interview. “This was not the case in Japan or in Europe.”

However, the same period of 30 years saw a disturbance of research and activity to try to reduce geriatric falls and potentially destructive consequences, from hip fractures and brain bleeding to limited mobility, persistent pain and institutionalization.

The American Geriatric Company has adopted up -to -date guidelines to prevent fall in 2011. The CDC presented a program called STEADI in 2012. The United States Preventive Services Group is recommended for exercise or natural treatment for older adults in 2012.

“There have been studies and interventions and investments and have not been particularly successful,” said Donovan Maust, a geriatric psychiatrist and researcher at the University of Michigan. “It’s a bad problem that seems to be getting worse.”

But prescription drugs lead to growth? Geriatrics and others investigating and prescribing practices question the conclusion.

Farley, a former New York Health Commissioner, who teaches at Tulane University, acknowledged that many factors contribute to falls, including natural harm and deterioration of vision associated with advanced age. alcohol abuse; and the dangers of people’s homes.

But “there is no reason to think that one of them has taken three times worse in the last 30 years,” he said, showing studies showing reductions in other high -income countries.

The difference, he believes, is the increasing use of drugs by Americans – such as benzodiazepines, opioids, antidepressants and gabapentin – acting in the central nervous system.

“The drugs that increase mortality are the ones that make you sleepy or dizziness,” he said.

Problematic drugs are enough to have an acronym: Frids or “drugs that increase the risk of falling”, a category that also includes various heart drugs and early antihistamines such as Benadryl.

Such medicines play an important role, agreed by Thomas Gill, a geriatric and epidemiologist at Yale University and a long -term researcher. But, he said, “there are alternative explanations” to increase mortality rates.

He mentioned the changes to the reference to the causes of death, for example. “Years ago, falls were considered a natural consequence of aging and no big case,” he said.

Death certificates often attributed deaths among the elderly to diseases such as heart failure instead of falls, making the mortality of falling occurring in the 1980s and 1990s.

Today’s super-85 coorde can also be weak and more sick than the older one was 30 years ago, Gill added, because modern medicine can keep people alive more.

Their accumulated lesions, more than the drugs they take, could make them more likely to die after a fall.

Another skepticist, Neil Alexander, Green, and falls expert at the University of Michigan and Va Ann Arbor Healthcare System, claimed that most doctors have occupied the dangers of parothers and prescribe them less often.

“The message was delivered,” he said. Given the alarms heard about opioids, benzodiazepines and related medicines, and especially for opioids and benzo together “, many primary care doctors have heard the gospel,” he said. “They know they don’t give the old Valium.”

In addition, recipes for certain autumn -related medicines have already declined or hit plateaus, even when mortality rates have increased due to falls. Medicare data shows that the use of lower prescription opioids since the beginning of a decade ago, for example. Benzodiazepine recipes for elderly patients have slowed, Maust said.

On the other hand, the use of antidepressants and gabapentin has increased.

Whether the use of drugs goes beyond all other factors, “no one deny that these agents are used too much and are used inappropriately” and contribute to the alarming increase in mortality rates from falling between the elderly, Gill said.

Thus, the ongoing campaign for “drainage” – stopping medicines whose possible damage exceeds their benefits or reducing their dosage.

“We know that many of these drugs can increase reductions of 50 to 75%” in elderly patients, said Michael Steinman, an old age at the University of California-San Francisco and co-director of the American research network, founded in 2019.

“It’s easy to start the drugs, but it often takes a lot of time and effort to stop patients from taking them,” he said. Doctors can pay less attention to drug shapes than to healthy healthy issues and patients may be reluctant to abandon the pills that seem to help with pain, insomnia, reflux and other age -related complaints.

Beer criteria, a list of medicines that are often considered irreparable for older adults, have recently published recommendations for alternative medicines and non -pharmacological treatments for frequent problems. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Exercise, natural therapy and psychological interventions for pain.

“It’s a real tragedy when people have this fact that changes life,” said Steinman, a co -chair of the Beer Committee in alternatives. He called on the elderly patients to raise the issue of the mumps themselves if their doctors do not have it.

“Ask,” Do any of my medicines increase the risk of falling? Is there an alternative treatment? “, He suggested.” Being informed patient or caregiver can put this on the agenda. Otherwise, it may not appear. ”

The young age is produced through collaboration with the New York Times.