In a recent review published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, The researchers surveyed the literature on avian influenza A (H5N1) mammalian infections over the past two decades. Their review covered two major panzootic periods – 2003 to 2019 and the ongoing 2020 to 2023 – and clarifies trends in H5N1 infections during these periods. Their findings suggest that while the main source of virus transmission remains contact with infected birds, mammal-to-mammal transmission is increasing. These alarming findings highlight recent mutations in H5N1 strains, underscoring the need for continued surveillance to mitigate a potential global pandemic.

Summary: Recent changes in patterns of mammalian infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) worldwide. Image credit: Jeremy Richards / Shutterstock

Bird flu in mammals?

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) is a severe viral disease caused by subtypes (H5 and H7) of type A. Over the last century, these viruses have caused repeated endemic waves, spreading rapidly and causing significant losses of the avian fauna in a wide range of species, especially poultry reared by humans.

Since 2003, however, HPAI A (H5N1) has been observed to breach kingdom barriers and jump from its avian hosts to mammals, resulting in two unprecedented panzootic events – 2003 to 2019 and the ongoing 2020 to 2023 period. These events have raised alarm bells in the scientific community because of the mutated H1N5 strains affecting endangered wildlife, the economic losses associated with infecting their livestock, and their potential for transmission to humans.

Limited reports of the ongoing panzootic period suggest that it is significantly more severe than that of 2003. It is predicted to be one of the worst panzootic events in recorded history in economic scale, geographic coverage, and animal morbidity and mortality. In the three years since the panzootic emerged, the virus has spread to four continents and a record 26 countries, infecting mainly mink, foxes, ferrets, seals and domestic cats, all of which have potential for transmission to humans.

Unfortunately, research on H1N5 and ongoing panzootics remains scarce and limited to the “grey literature” (unreviewed records and reports from government databases and websites). Understanding the evolution of the H5N1 virus and the mutations that allow emerging strains to far surpass their progenitor virus in virulence and spread across species will better equip policymakers and scientists with the information needed to attenuate the ongoing panzootic before exploding into a full-blown pandemic.

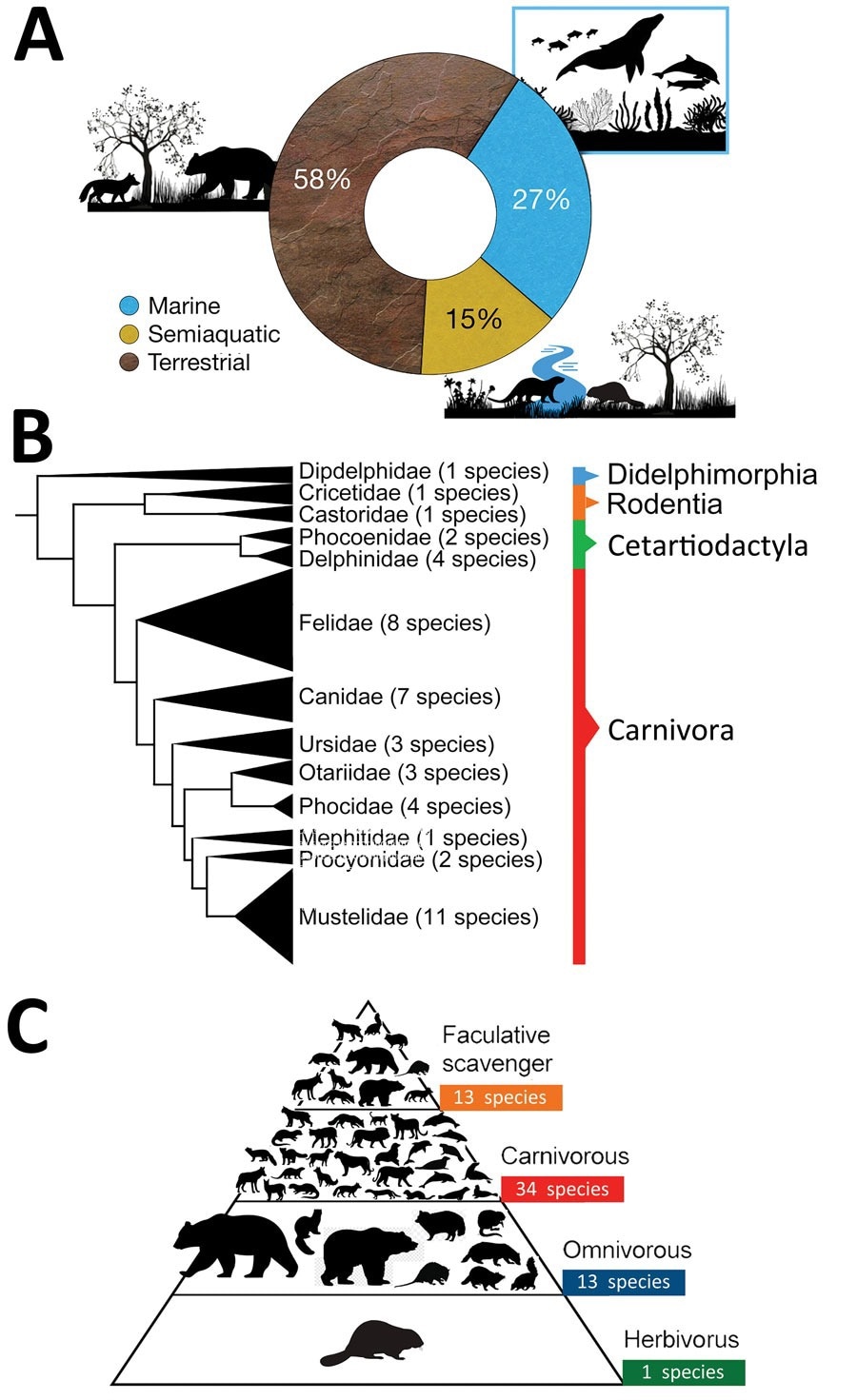

Characteristics of mammalian species globally affected by the current panzootic highly pathogenic influenza A (H5N1) virus (2020–2023). A) Habitat of mammalian species affected by H5N1. B) Phylogeny of affected mammalian species (tree constructed using iTOL version 5 after Letunic and Bork, from DNA sequence data available in Upham et al.). C) Trophic level (facultative scavenger, carnivore, omnivore, or herbivore) of mammalian species globally affected by H5N1. Some of the omnivorous and carnivorous mammals included in the pyramid (n = 13) also consume carrion. Thus, they are also considered optional scavengers and are incorporated at the top of the pyramid.

About the study

In the present review, researchers compiled and analyzed the scientific literature on natural H5N1 mammalian infections (including humans) and compared findings from the current panzootic with those from previous waves of H5N1. The review focuses on the number and habitats of infected species, their phylogeny, sources of infection and necropsy findings. They further investigate the viral mutations that enable cross-species transmission and elucidate potential risks to biodiversity and human health.

Data were collected from the online databases Scopus and Google Scholar, with searches divided into two periods – 1996 to 2019 and 2020 to 2023. Studies based on serology were excluded from analyzes due to uncertainty about the timing of infection, which may affect the diagnostic results. In addition, the World Organization for Animal Health, the United Kingdom’s Animal and Plant Health Agency, and the United States (US) Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Service were consulted for updated information on the current panzootic.

Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) were compiled for information on human infections. Finally, conservation statuses of infected species were obtained from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, their diet and habitats from MammalBase, and H5N1 sequence data from Upham et al. (2019).

Study findings

Literature review of the database revealed 59 publications on H5N1 mammalian infections, 23 of which discussed previous waves of H5N1 and 36 on ongoing panzootics. The scientific interest in the ongoing panzootic is immediately apparent – more mammalian infection data have been generated in the past three years than in the previous 23.

Worryingly, while previous waves reported 10 infected countries spread across three continents (Asia, Europe and Africa), the ongoing panzootic has already spread to 26 countries across Europe, South America, North America and Asia. Limited trials and reports from other nations suggest these findings are underestimates.

“Our review shows that the H5N1 virus is expanding its geographic range to new continents such as North and South America. This fact is of concern because when an emerging pathogen reaches naïve populations, the consequences for biodiversity can be devastating, especially for endangered species.”

Surveys of the number of species affected reveal that while previous panzootics cumulatively infected nine mostly terrestrial and semi-aquatic species, the current panzootic has already been detected in more than 48 mammal species, including 13 marine mammal species. Peru, Chile and Argentina have reported thousands of deaths from seals and similar mammals (e.g. the American sea lion [Otaria flavescens]), almost resulting in localized extinction events.

The cost to biodiversity is critical – so far, bird flu has affected four Near Threatened, four Endangered, three Vulnerable and one Critically Endangered species compared to previous panzootics, which cumulatively infected two Endangered and two Vulnerable species.

There are similarities with previous pandemics – most mammals affected are carnivores (mainly apex and mesocarnivores) and scavengers, which correspond to the most likely sources of infection – close contact (including ingestion) with dead or dying birds or infected carcasses.

…in the year 2004, a total of 147 tigers and 2 leopards housed in zoos in Thailand became infected and died after consuming contaminated chicken carcasses. In the current panzootic, the first case of H5N1 infection in mink in Spain was probably caused by contact with infected birds (perhaps seagulls).

At least five publications have reported an alarming trend in virus adaptation – H5N1 strains with new mutations that may allow mammal-to-mammal transmission have been identified. If these strains spread, models suggest a global pandemic could quickly emerge, causing unprecedented biodiversity and economic loss.

Finally, H5N1 was found to have spread and infected at least 878 people and resulted in 458 deaths (52% mortality) with close contact with animals (especially poultry) considered to be the main route of transmission.

“So far, no evidence points to human-to-human transmission and the risk of a pandemic event still appears low. However, one of the most serious influenza viruses to affect humans (ie, the Spanish flu [1918–1919]) was developed from an avian influenza virus adapted to humans, which should be taken into account when assessing the risk of dissemination. Governments must take responsibility for protecting biodiversity and human health from diseases caused by human activities. If we hope to preserve biodiversity and protect human health, we must change the way we produce our food (poultry, in this case) and the way we interact with and affect wildlife.”