Babies of all species, from mice to humans, quickly forget things that happen to them – an effect called infantile amnesia. A type of brain immune cell called microglia can control this kind of forgetting in young mice, according to a study published Jan. 20u in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Erika Stewart, of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, and colleagues.

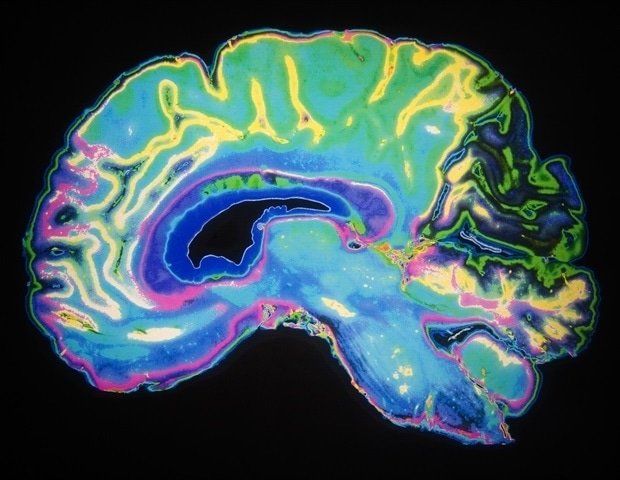

Infants and young children grow quickly and take in vast amounts of information as they grow. However, there is a lack of episodic memory from this early developmental period—memory of past events such as a first birthday party or the first day of preschool. To better understand how this infantile amnesia works, the authors of this study inhibited the activity of microglia—the brain’s main immune cells—in very young mice and tested how well they could remember a frightening experience. They also looked at markers of microglia in two memory-related brain regions—the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and the amygdala.

The researchers found that when microglia activity was suppressed, with less activity in the hippocampus and amygdala, the young mice had better memories of their fearful experiences. The scientists also used glowing tags to identify neurons—engram cells whose activity is specifically related to memory formation. When microglia were inhibited in infant mice, the engram cells became more activated, suggesting enhanced memory recall.

In previous work, scientists discovered that mice born to mothers with activated immune systems do not have infantile amnesia. When the scientists inhibited microglia activity in those offspring without infantile amnesia, they were able to restore it—presumably restoring normal access to their memory. While other cell types may be involved, the authors suggest that microglia are essential for infantile amnesia in mice and could help shape memory-forming networks in the brain.

Microglia, the resident cells of the central nervous system’s immune system, can be thought of as the “memory managers” in the brain. Our work highlights their role in infantile amnesia specifically and suggests that there may be common mechanisms between infantile amnesia and other forms of forgetting – both in everyday life and in disease.”

Erika Stewart, Trinity College Dublin

Co-author Tomás Ryan notes: “Infant amnesia is probably the most ubiquitous form of memory loss in the human population. Most of us remember nothing from the early years of our lives, despite the fact that we had so many new experiences during those formative years. This is an overlooked topic in memory research, precisely because we all accept it as a fact of life.

Ryan adds, “But what if these memories are still present in the brain? Increasingly, the memory field sees forgetting as a ‘characteristic’ of the brain rather than a ‘bug’. Infantile amnesia can give us insight into how forgetting happens in the brain in general. Being able to manipulate infantile amnesia opens doors to new ways of imagining how learning and forgetting might work during the early years of life.

Ryan notes, “It will be interesting and important to identify people who do not experience infantile amnesia. To learn how their brains work and to understand their experience of early childhood education.”