Scientists have identified a promising target for the treatment of a devastating autoimmune disease that affects the brain.

The discovery could lead to the development of new treatments for a disease caused by an attack on one of the key neurotransmitter receptors in the brain, the NMDA receptor. It also increases the potential for a blood test to detect a sign of the condition and for early treatment with existing treatments.

The study from Oregon Health & Science University was published today in the journal Advances in Science.

The condition may be best known from the best-selling autobiography and 2016 movie, “Brain on Fire.” The condition is considered a rare disorder that affects about 1 in a million people a year, mostly people in their 20s and 30s.

The condition is triggered by an autoimmune attack on the brain’s NMDA receptor, mediated in part by anti-NMDA receptor autoantibodies, and is characterized by mental changes, severe memory loss, seizures and even death.

In the study published today, the researchers identified specific sites on an NMDA receptor subunit that, if blocked, might reverse the progression of the disease. Lead author Junhoe Kim, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the OHSU Vollum Institute, examined anti-NMDA receptor autoantibodies from a mouse model that OHSU researchers previously engineered for this purpose. He then compared it to images of the same autoantibodies isolated from people with the disease.

The location of the binding sites in the mouse model matched those in people with the condition.

“We have really solid evidence because the autoantibody binding sites that Junhoe identified overlap with those from humans,” said senior author Eric Gouaux, Ph.D., a senior scientist at Vollum and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “We are now focusing on this area as literally a hot spot for the interaction that underpins at least one component of the disease.”

Kim said investigators generally knew where to look.

“From previous studies, people knew where the antibodies might bind,” he said. “But we collected the entire panel of autoimmune antibodies from a mouse model of the disease and clarified where specifically they bind to the receptor.”

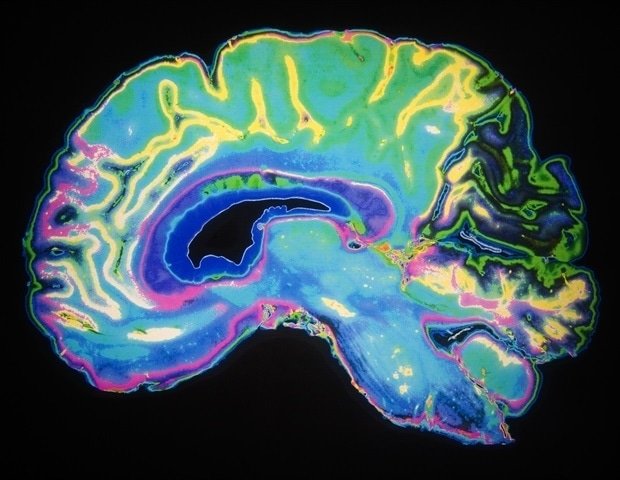

They made the discovery using near-atom imaging at the Pacific Northwest Cryo-EM Center, housed on OHSU’s South Waterfront campus and one of three national centers for cutting-edge imaging technology. It is jointly operated by OHSU and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and funded by the National Institutes of Health.

“Almost all antibodies bind to a single region of the receptor that happens to be the part of the receptor that is easiest to target,” Gouaux said. “It’s a super exciting result, actually.”

Co-author Gary Westbrook, MD, a neurologist and senior scientist at the Vollum Institute, said the discovery could pave the way for drug companies to develop a therapeutic agent that could specifically target the binding sites that cause the disease. Current treatments that include immunosuppression don’t always work, and patients can relapse, he said.

“They definitely need more specific approaches,” he said.

In addition to Kim, Gouaux and Westbrook, the authors included Farzad Jalali-Yazdi, Ph.D., and Brian Jones, Ph.D., of OHSU.